The crypto industry’s debanking smokescreen

Cryptocurrency companies have co-opted legitimate concerns about banking discrimination to fight regulation — and Congress is buying it

Last week, Congress held two hearings about Americans losing access to banking services. In theory, everyone agreed this was a serious problem requiring urgent attention. In practice, they weren't even discussing the same issue. Democrats described Muslim Americans broadly reporting denial of banking services, immigrants locked out of the banking system for wiring money overseas or participating in traditional community lending practices, and low-income individuals being forced to pay high fees simply because they didn’t carry a balance in their bank accounts. Republicans and their crypto-friendly Democratic allies were instead laser-focused on a different claimed victim: the cryptocurrency industry, which alleged it was being systematically cut off from banking services through a shadowy government pressure campaign dubbed “Operation Choke Point 2.0”.

These seemingly unrelated conversations could occur side by side because they share an umbrella term: “debanking”. At its simplest, it means the practice of closing bank accounts or refusing other financial services to prospective bank clients. But the term has also come to describe the specific issue of discriminatory debanking: where groups of people are disproportionately denied access to financial services for reasons unrelated to banks’ normal, individualized risk assessments. This can be based on various characteristics, including protected characteristics such as race or religion; on financial characteristics, such as income status or the frequency with which people make cash or international wire transactions; or on industries with which a client is either directly involved or indirectly associated.

This is an important point to clarify: when crypto industry figures, Congresspeople, and writers such as myself are using the term “debanking” right now, we’re usually using it more specifically to refer to improper debanking — not the everyday practice of banks closing accounts because a client has been determined unsuitable due to specific risk analysis.

Historical background

Debanking has been a recurring topic of conversation in Congress even before the most recent crypto-fueled resurgence in interest. In the recent past, Democrats have mostly focused on discriminatory debanking disproportionately targeting groups including Muslim or Armenian Americans, immigrants who tend to make a large number of international wire transfers to family who remain outside of the United States, those who participate in community banking programs like susus (who are often people of color and/or immigrants), or those with criminal backgrounds. A November 2023 New York Times story on systemic debanking of such groups prompted inquiry from Democratic Representatives Omar (MN), Tlaib (MI), and Pressley (MA) and Senators Warren (MA) and Sanders (VT).12 Democrats have also regularly expressed concern from financial inclusion perspectives, seeking to level the playing field for low-income individuals who face denial of financial services or excessive fees and penalties simply because they don’t carry a high bank balance.3

Conversely, debanking conversations over the last few years from Republicans have typically revolved around concerns that banks have unfairly denied services to those with right-wing political beliefs or who are associated with Christian religious groups.45

In slightly more distant history, there were substantial debanking conversations about Operation Choke Point: an improper practice during the 2010s in which the American government pressured banks to deny services to broad categories of businesses and individuals associated with various industries, including firearms sales, payday lending, and sex work.

Even since the formal end of Operation Choke Point, members of both parties have continued to express concerns that people and companies associated with specific industries are regularly debanked, although these conversations do not always involve the claims of direct government pressure that characterized Operation Choke Point and made it so problematic. Democrats have generally focused these concerns around industries such as cannabis,6 whereas Republicans have focused on those such as firearms, fossil fuels, and private prisons4 — though it should be noted that support and opposition in these areas is not always neatly split across party lines.

Crypto hijacks the debanking debate

Against this complex backdrop of legitimate debanking concerns spanning racial discrimination, religious profiling, and industry-based exclusion, the cryptocurrency industry has recently mounted its own aggressive campaign about banking access. The industry has pushed a narrative that they too are victims of discriminatory debanking — specifically through what they've dubbed “Operation Choke Point 2.0”.

As I’ve discussed before [I71, 73, 74, 76], powerful figures in and outside of the crypto industry have been broadly claiming that the FDIC and other financial regulators have been engaged in a nefarious pressure campaign to force banks not to offer services to crypto companies or people associated with crypto. Aided by over $130 million in crypto industry spending on Congressional races this cycle, these claims have made their way to the top of some Congresspeople’s lists of concerns. The Senate Banking Committee held a hearing on February 5 titled “Investigating the Real Impacts of Debanking in America”, and the House Financial Services Committee held one the following day, rather more pointedly dubbed “Operation Choke Point 2.0: The Biden Administration’s Efforts to Put Crypto in the Crosshairs”. On the morning of the Senate hearing, the FDIC also released a nearly 800-page document containing 175 records of correspondence between the FDIC and banks and other financial institutions pertaining to crypto.

But when it comes to the crypto industry’s claims, there has been a lot of disagreement regarding their veracity. Many cryptocurrency companies and individuals associated with the industry have come forward to say that they have lost access to banking, blaming it on a coordinated government effort under the Biden administration via the FDIC and other regulators. Republicans and some crypto-friendly Democrats have been quick to echo these claims. However, some, including some of the Republican-invited witnesses brought to testify in front of Congress, have disagreed (apparently to at least one Republican Congressman’s surprise):

Mike Ring, CEO of Old Glory Bank (“the pro-America, online bank for freedom-loving Americans”), answers questions from Senator Kennedy (R-MS)

Representative Al Green (D-TX) was blunt in his opening statement, describing “Operation Choke Point 2.0” as “a fake program never initiated by the Biden Administration” and arguing that regulators asking banks to “exercise caution” and “consider the risk associated with the cryptocurrency industry does not amount to debanking”.

Representative Tlaib (D-MI) also echoed this point: “I’d like to discuss facts motivating today’s hearing and Coinbase’s and its consultants’ complaint against the FDIC. The claim that ‘starting’ — you’re probably familiar with this — ‘starting in 2022, federal financial regulators have taken concerted steps designed to debank the digital asset industry.’ But what’s interesting about this timeline, and maybe Ranking Member you’d find this interesting, what actually happened around 2022? Folks are forgetting. I mean they were going to play dumb but we’re not — we know what happened. Investors lost $2 trillion during what we call ‘crypto winter’, and a whole host of crypto and digital asset companies went belly up including FTX and Celsius. And in early 2023 we saw Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and Silvergate fail, with crypto playing a huge role in it.”

Examining the latest FDIC documents

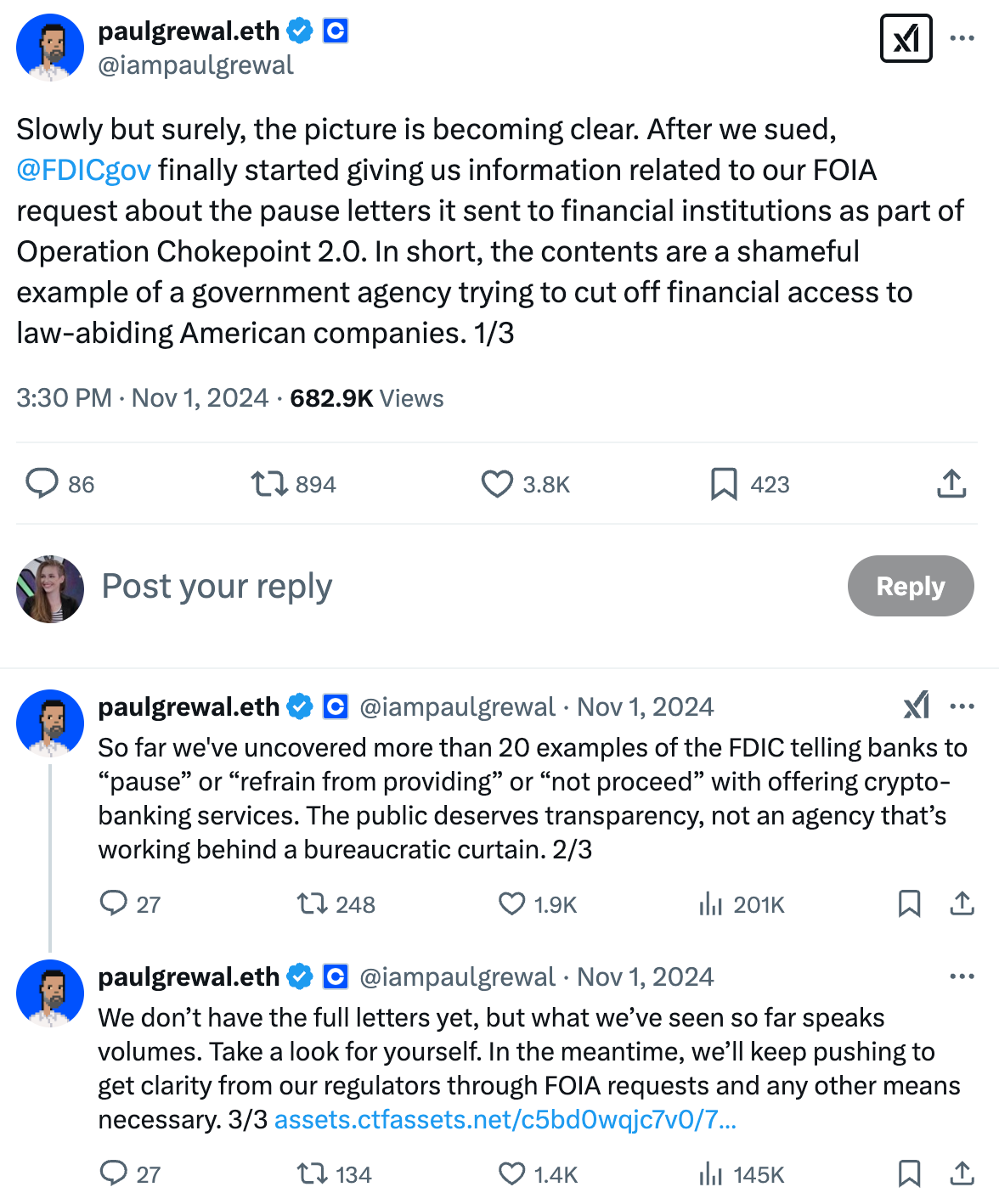

In parallel to Congressional pressure, the crypto industry has been working to prove that they have been systematically debanked via pressure on banks from the FDIC, mostly — as Tlaib referenced — by trying to obtain FDIC communications with banks through FOIA requests and then a lawsuit filed by Coinbase. As I wrote about the first release of FDIC documents [I73], their contents didn’t really say what Coinbase and other crypto advocates claimed they said:

The documents actually reflect mostly requests for more information about blockchain-related services provided or used by banks themselves, where the FDIC was seeking to do things like “gain an understanding of how the bank will ensure continued safe and sound operation as this activity is implemented”. Where the FDIC did request banks pause activities, it was again where those banks were looking to themselves provide crypto services or offer crypto assets directly to customers (such as multiple emails addressing one or more banks wanting to sell, or already selling, crypto to their customers via web or mobile banking apps), and the FDIC explained that there was not an approved regulatory process for FDIC-supervised banks to do such a thing.

Despite this, Coinbase Chief Legal Officer Paul Grewal claimed he was summarizing when he posted on Twitter at the time that, “in short, the contents are a shameful example of a government agency trying to cut off financial access to law-abiding American companies”.

The most recent dump of documents is highly similar to the first and consists of communications between banking regulators and banks that stemmed from an April 2022 request — issued shortly after the Terra/Luna collapse [W3IGG] kicked off cascading failures that would continue to decimate the overleveraged cryptocurrency industry throughout that year — that “All FDIC-supervised institutions that intend to engage in, or that are currently engaged in, any activities involving or related to crypto assets (also referred to as ‘digital assets’) should notify the FDIC” to “allow the agency to assess the safety and soundness, consumer protection, and financial stability implications of such activities.”7

What the documents actually show

Once again, the crypto industry is claiming that this lengthy trove of documents contains a smoking gun proving that the FDIC was forcing banks not to serve the crypto industry. Once again, the reality of the documents does not support such a claim.

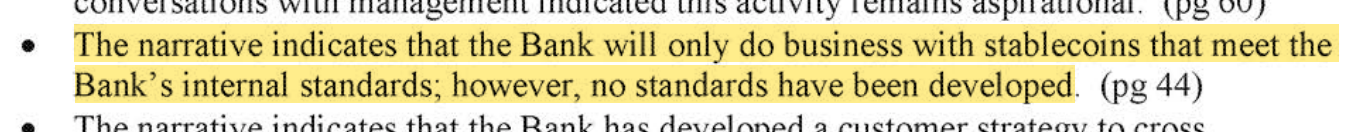

As with the last release, many of these documents are communications between the FDIC and banks that were not to do with banks denying depository accounts to clients in or associated with the crypto industry (which could be categorized as debanking), but rather with banks trying to offer crypto services themselves, including by adding bitcoin purchases to their mobile banking apps or installing bitcoin ATM kiosks in their lobbies. Questions around these activities seem well within banking regulators’ remit, and it seems deeply misleading to me for crypto companies complaining that their industry is being debanked to, when asked for supporting evidence, point to documents describing banks being questioned about or asked to pause programs to sell customers bitcoin in their online banking portals. It’s also entirely understandable to me that the FDIC seems particularly concerned in multiple communications about various banks potentially implying that their crypto offerings are subject to FDIC insurance, given that victims of several companies that collapsed in 2022 had been under this false impression [I1, 41, several W3IGG entries].

Most of the communications between the FDIC and banks looking to offer crypto products consisted of questions about the specifics of their offerings, and then ongoing discussions about their replies. Coinbase’s Grewal was among the witnesses for the House hearing, and he suggested that the FDIC asking questions was itself improper: “Over and over again the FDIC bludgeoned the banks with an onslaught of examinations and questions until the banks relented under the pressure.” Grewal’s fellow witness Austin Campbell, the CEO of the WSPN stablecoin company, made similar claims, stating that the FDIC documents “indicate” that “they will just ask you questions endlessly and tell you that you need to get permission from the regulator to engage in these activities and helpfully they’ll never stop asking questions. Right? This could be two years straight of questions with no end point, no finish line, no clear articulation as to what they’re trying to learn and at some point it just becomes a repetitive cycle and it’s clear the answer is no.”

The FDIC documents don’t support the witnesses’ characterizations. While there are long lists of detailed questions directed towards banks considering launching crypto products of their own, the inquiries seemed to me to be fairly reasonable, as do follow-up questions about banks’ replies. None of the back-and-forth conversations published in the FDIC’s latest release reflect the agonizing, years-long interrogations that either executive described. In fact, many of these communications dredged up enormously concerning responses from the banks, serving to only further justify this type of questioning. I will highlight only a select few:

![The form's responses to principal ownership, length of time in business, and regulatory oversight of the company do not accurately reflect the entity that the bank is contracting with, the entity's organizational structure, or affiliate services. [begin highlight] The form states that [redacted] has been operating since [redacted]; however, [redacted], the entity that the bank contracts with did not exist in [redacted]. [end highlight] The form also states that the regulators](https://www.citationneeded.news/content/images/2025/02/Screenshot-2025-02-12-at-2.15.12-PM.png)

![these customer expectations were generated from [redacted] and included little to no support. [begin highlight] Furthermore, those projections were likely generated when bitcoin prices were rapidly appreciating in comparison to the US Dollar and did not consider any type of range or pullback in the market. [end highlight] Management should revisit the report and consider a range of results that incorporate different levels of adoption and transaction volume.](https://www.citationneeded.news/content/images/2025/02/Screenshot-2025-02-12-at-2.17.43-PM.png)

![The [redacted] report identified more than [redacted] consumer complaints against [redacted] made to the Better Business Bureau. Management did not document its review of the complaints or receive any other information on the complaints not provided. The [redacted] Report does not provide sufficient information to determine if any of the vendor-related complaints involve custody-specific unfair or deceptive acts or practices or other consumer compliance concerns. Furthermore, there was no discussion on whether [redacted] considered complaints in its assessment. (v2, pg 271-280) The [redacted] Report identified more than [redacted] consumer complaints against [redacted] to the Ripoff Report and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). [redacted] included [redacted] complaints from Ripoff Report and no complaints from the CFPB.](https://www.citationneeded.news/content/images/2025/02/Screenshot-2025-02-12-at-2.21.16-PM.png)

![The risk assessment is not commensurate with the potential risk exposure posed. Management approved a Bitcoin Program risk assessment prepared by [redacted] with minimal edits, which lacked independence, lacked a discussion of controls in key areas, or outlined controls/mitigants that did not exist or were inaccurate.](https://www.citationneeded.news/content/images/2025/02/Screenshot-2025-02-12-at-2.23.12-PM.png)

There are some portions of the FDIC documents that discuss banks merely providing depository banking services to customers in the cryptocurrency industry or associated with crypto, and that was what I was most interested in, as directives from the FDIC to deny these types of services to those customers wholesale would be something much more reasonably described as a Choke Point-style debanking campaign.

In the FDIC’s most recent document release, there were a handful of types of communications that fell into this category. Some were inquiries by banks to the FDIC as to whether the FIL directive to report “activities involving or related to crypto assets” included when they merely offered depository banking services to crypto-related companies. This definitely seems like something the FIL should have been clearer about, as in one case even the FDIC employee who responded wasn’t sure of the answer and had to ask another office (although they instructed the customer to proceed under the assumption that this was not covered by the FIL).8 However, in several other letters, the FDIC clarified that no, merely offering fiat banking services (including loans) to crypto companies did not fall within the scope of the FIL — something it seems they would be unlikely to say if they were indeed trying to systematically prevent banks from serving crypto companies.910 In one case, there was some question about whether a relationship with a bank fell within scope, and the FDIC seemed to determine it did simply because bank management seemed to have very little understanding themselves of the proposed relationship.11

Some other documents contained discussions between banks and the FDIC about banks’ crypto-related depository customers, but seemed fairly run-of-the-mill. In one FDIC memo, representatives from the bank and the regulator discussed crypto customers with high cash activity, and the need to apply more diligence to understand those cash transactions since they were high risk. The FDIC representative in that case was explicit that “we are not asking the bank to exit these relationships”, and a bank representative expressed that they believed “most of the recommendations [pertaining to digital asset customers] were really good”.12 A very similar conversation occurred between the FDIC and a bank that was providing banking services to a Bitcoin ATM operator, where a bank representative expressed concern that the FDIC “has made a determination that banking these [redacted] customers is not ok”, and an FDIC representative “reiterated that we are not requiring the bank to exit the business, but to conduct more due diligence, look at the potential red flags, and provide the bank’s board with the results. The decision whether or not to continue to bank these customers should be a business decision made by the board after review of the additional information.”13 In a few cases there were broad questions from the FDIC to banks they already knew had crypto-related depository and loan customers, for example a few days after the FTX collapse, when an FDIC case manager asked about “any trends you are observing” with such accounts (likely concerned about the possibility of a bank run) and was informed “All is well.”14

There were also conversations about banking relationships with cryptocurrency companies that involved not only depository accounts but “for benefit of” (FBO) accounts: where a company holds customer funds in an account with the bank for the benefit of their customers. In these cases, the FDIC asked a number of fairly standard questions pertaining to account structure, size, capital requirements, and so on.15

In several cases, banks described closing accounts belonging to crypto customers, but these seemed to me to be of the banks’ own volition and as a result of their internal risk management decisions.1016

Oversight or overreach?

The crypto industry has argued that there does not need to be a plain-text directive from a regulator that “you may not provide banking services to crypto industry customers” to establish that the FDIC was pressuring banks not to serve customers from that industry. I firmly agree. And I found Representative Green’s question about whether anyone has “read some document from the Biden Administration or some regulator indicating that there is an Operation Choke Point 2.0? That said ‘2.0’?” — as though they would have to brand it that themselves in writing in order for such a pressure campaign to exist — to be ridiculous.

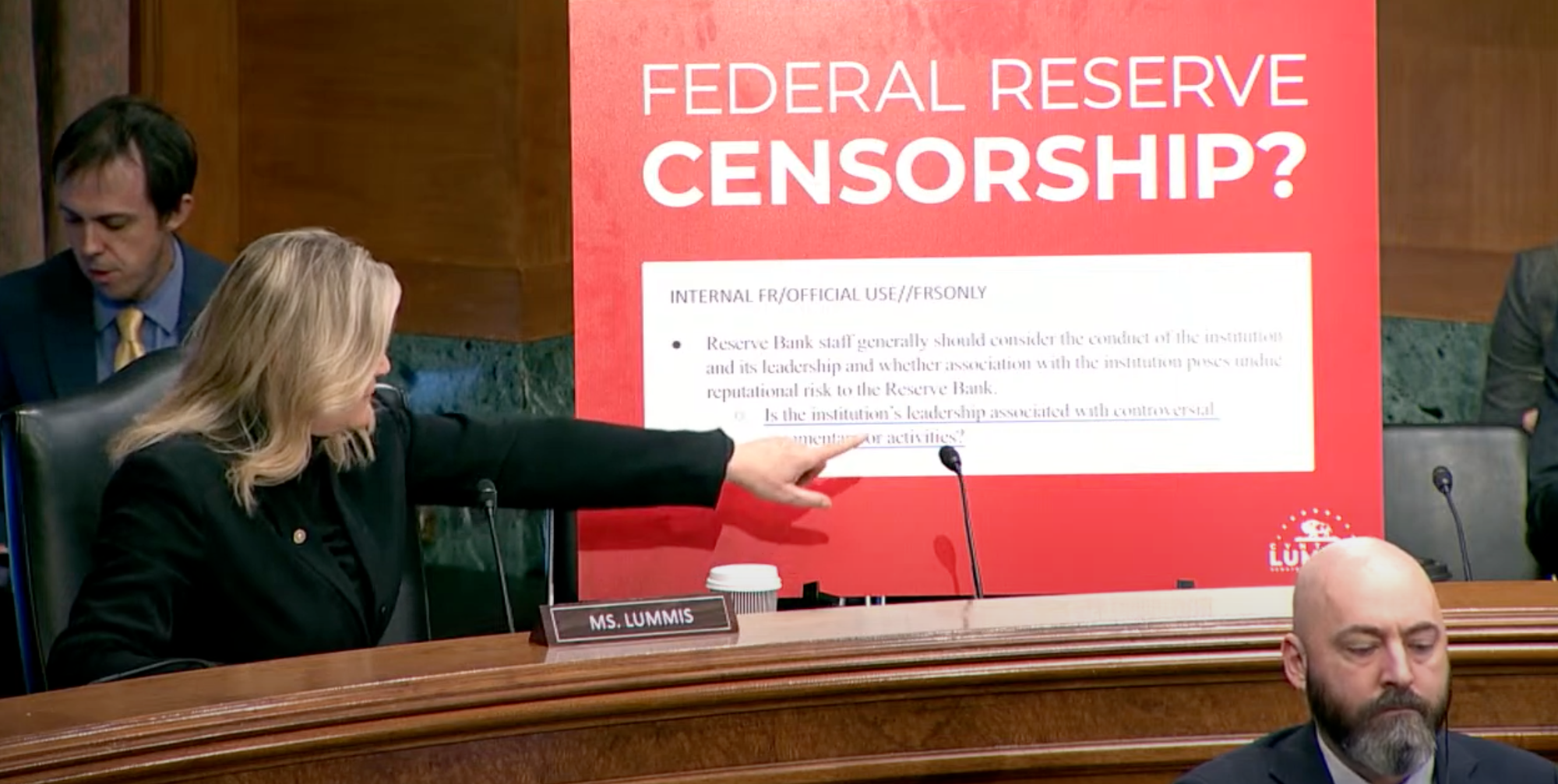

Indeed, some evidence presented at the hearings did raise legitimate concerns about regulatory overreach, even if it didn't specifically support claims of an anti-crypto agenda. For instance, Senator Lummis (R-WY) presented a troubling screenshot from a Federal Reserve manual instructing staff to “consider the conduct of the institution and its leadership and whether association with the institution poses undue reputational risk to the Reserve Bank” and asking whether “the institution's leadership associated with controversial commentary or activities?” Such guidance could certainly enable discriminatory treatment based on subjective judgments about what constitutes “controversial” activity, even if it wasn't specifically targeted at cryptocurrency companies, and I was just as delighted as some of those with very different political beliefs to mine when Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell promised during his regular Congressional report to ensure it was removed.17

(I would, however, be remiss to not point out the great hypocrisy from Republicans who spent much of the hearing denouncing banks who might deny services to those expressing right-wing political beliefs, but who seem perfectly fine with the long list of First Amendment violations well underway in the White House.)

I also think that we are in a world where banking and other financial regulators have been burned by the past collapses of the cryptocurrency industry, which has very much proven itself to be a high-risk industry, and have determined that they need to apply additional scrutiny. Where Representative Green did have a reasonable point was when he stated, “I wouldn't want to be a regulator. It's a tough job because if a bank fails then you didn't do enough and then if it somehow doesn't give you the kind of regulation that you want it's too much.” (Indeed, Representative Hill (R-AR) demonstrated this dichotomy as applied to crypto companies when he opened the hearing by blasting the SEC, stating “one of our witnesses today, Coinbase, an American company registered as a public company with the SEC, was treated poorly and FTX, a criminal organization, wasn't even investigated.”)

Simultaneously, we are in a world where the cryptocurrency industry has proven itself to be violently allergic to any and all regulation — including legitimate regulatory enforcement — and has spent years portraying that regulation as not only unwanted but as improper and even illegal. We are in a world where Congresspeople have campaigned on this very subject. And we’re in a world where crypto companies are hell-bent on establishing that they were victimized by regulators so as to obtain ammunition for their attacks against those regulators, as well as attacks against laws that would limit them from doing any and all activities they think might be profitable — systemic financial risk and consumer protections be damned.

There's also an important dynamic at play that the crypto industry conveniently ignores: in the absence of proper consumer protection regulations on cryptocurrency companies themselves, much of the burden of protecting consumers has fallen to banks. When crypto users are scammed or hacked and crypto companies refuse to make them whole, these users often attempt to claw back their losses through their banks. Banks face costly chargebacks and fraud claims, while bearing the customer service burden of dealing with victims of crypto scams who are often treated with outright hostility by the crypto firms they use. This creates a legitimate business reason for banks to be wary of serving crypto customers or companies, entirely separate from any regulatory pressure. The crypto industry's vigorous opposition to consumer protection regulations has, ironically, contributed to their own banking difficulties by forcing traditional financial institutions to act as de facto consumer protection mechanisms.a

In this world, it is not surprising that we are in a situation where different people can look at the same set of documents and some will conclude that the regulators are simply doing their jobs by ensuring banks are doing adequate risk management with high-risk customers, while others conclude that regulators are improperly pressuring banks to not provide services to those customers at all. This is particularly the case because the documents are partially redacted, leaving some sentences and even entire communications open to very different interpretations depending on how the reader’s brain tries to fill in the blanks.

However, the crypto industry’s suggestions that these FDIC document releases contain incontrovertible, smoking-gun proof of some Biden administration or regulator directive are hyperbole aimed at misleading those who don’t have the time or interest to read several hundreds of pages of documents (our Congresspeople among them, I suspect). The same types of attempts to mislead are also evident in their treatment of recent comments by FDIC Acting Chair Travis Hill, who had previously served as Vice Chairman of the FDIC since January 2023 and has worked at the agency since 2018. When Hill acknowledged shortly after being installed as Acting Chair that “Over the past few years, there have been various accounts of individuals and businesses associated with the crypto industry losing access to bank accounts without explanation” — a simple statement of fact about complaints that have been made — the industry treated it as confirmation that improper debanking occurred. If they truly believed Hill was confirming improper debanking pressure was being applied by the FDIC, their calls for his resignation should be deafening — after all, he would have held a powerful role in overseeing the very activities he condemns, and he himself stated later in that speech “there is no place at the FDIC for anyone who has pushed — explicitly or implicitly — banks to stop serving law-abiding customers”.

This pattern of selective interpretation and opportunistic outrage is not limited to their treatment of Hill's comments, however. Their attacks on those who have not claimed that crypto companies have been denied bank accounts, and who have not claimed that it’s impossible that there was government pressure to debank crypto companies, but who have simply pointed out that the supposedly firm evidence of a governmental anti-crypto debanking campaign is anything but, demonstrate that their goal is not to uncover the truth about debanking, but to advance their dubious narratives in service of their policy agendas [I74].

It’s also worth noting that the crypto industry's claims of a government-led debanking campaign are essentially unfalsifiable, given the lack of public access to private government documents and correspondence. Yet, despite now having a Republican-controlled House, Senate, and Presidency, with pro-crypto appointees installed throughout regulatory agencies and Elon Musk and his team of interns rooting around in every government database they can get their hands on, and a new FDIC chair apparently willing to order the release of considerably more documents than his predecessor, the industry has still failed to produce any strong evidence to support its claims. This lack of proof, even with the deck stacked in their favor, is telling. Perhaps they will say they just need more time, but if the evidence of a coordinated debanking campaign were as clear-cut as the industry claims, it's likely that we would have seen it by now. Instead, they seem determined to simply claim it exists, and hope no one notices they haven’t produced it. In this case, we are expected to “trust, don’t verify”.

A murky path forward

The good news in all of these hearings and conversations is there seems to be widespread bipartisan acknowledgment that debanking happens, and that it’s a problem. The bad news is that there’s very little agreement around who is suffering as a result of debanking, or what to do about it.

When Democrats like Representative Tlaib and Senator Warren raise concerns about racial or religious minorities being disproportionately denied access to banking services, Republicans remain deafeningly quiet about racial discrimination in access to banking (with the exception of Senate Banking Committee Chair Tim Scott (R-SC), who likened the crypto industry’s supposed debanking to the redlining against his Black grandfather and mother, but who otherwise seemed to treat such issues as a thing of the past).

When some raise concerns about denial of banking services to firearms dealers, others respond that banks should be allowed to individually decide to do or not to do business with whomever they like, and that they should be permitted to protect their banks’ reputations by not serving groups their customer base may disfavor.18b

When people argue that low-income individuals need to be provided banking services, others suggest that no one should force banks to take on the risk of a client who may be more likely to bounce checks or improperly manage their finances.19c

And some even seem to disagree with themselves, taking inconsistent stances based on the victim of the debanking. For example, in September 2023, Senator Ricketts (R-NE) led opposition to the SAFER Banking Act, highlighting money laundering risk and suggesting that limiting banking access to marijuana businesses would help him further his opposition to the marijuana industry (he alleged marijuana causes “significant mental health damage to youth” and “is associated with psychosis, motor vehicle accidents, respiratory problems, and low birth weight”).20 Now, however, he brushes aside money laundering concerns when crypto is involved, and argues that “It undermines the rule of law in our country if regulators start pushing an agenda of what they want to see, what kind of businesses you do business with versus what you’re allowed to do. ... A legal business should not lose access to the banking system just because they deal in firearms or crypto or something like that because a regulator doesn’t like that. That’s just simply wrong. But that’s what we’ve seen of course out of the last two administrations: it was mentioned earlier about Operation Choke Point 1.0 under the Obama administration and firearms dealers for example that were disfavored, were prejudiced against and [regulators] tried to force out of the financial system.”21

As for what to do with it, the leaders of this crusade against supposed crypto debanking can’t even seem to agree among themselves. Some of the Republicans say it’s an issue with the regulators, others say it’s an issue with the bankers. Some want to see sweeping changes at the regulatory level, while others — including the crypto industry’s top-funded Congressperson this cycle, Bernie Moreno (R-OH) — want to just let the free market sort it out, saying “it’s competition that ultimately makes this go away” and “we need more competition in banking, that will fix us.”

Meanwhile, the one agency most involved in handling debanking complaints has been forced to pause work and is currently being dismantled.22 At the most recent Senate hearing, Ranking Member Elizabeth Warren came prepared with analysis of thousands of complaints filed with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) by customers who had lost access to their bank accounts without any explanation or opportunity for appeal.23 Several other Democratic Congresspeople raised the alarm during these hearings about the shutdown of the CFPB and its impact on people who are being shafted by banks, financial services companies, and fintechs, to be met with silence from Republicans on the other side who apparently are not concerned with that kind of debanking — or at least not concerned enough about it to stick their neck out against shadow President Elon Musk — and are only concerned about the alleged debanking of their crypto benefactors.

The crypto industry’s co-opting of legitimate debanking concerns represents a particularly cynical form of regulatory theater. Companies like Coinbase claim to be champions fighting discriminatory banking practices while simultaneously celebrating the shutdown of the CFPB — the very agency most equipped to tackle systemic debanking. When Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong took to Twitter to celebrate Musk’s attempt to shutdown the CFPB as “100% the right call”, describing the Bureau as “unconstitutional” (it isn’t24) and “an activist organization that has done enormous harm to this country”, he revealed the industry’s true priorities.25 Debanking is suddenly less of concern when the same group that is most equipped to tackle it has proposed consumer protections for crypto customers [I73] that could cause Coinbase to have to reimburse some of the $300 million or so stolen from its customers over the past year alone [I74]. “Debanking” is a crypto rallying cry only to the extent that it supports their deregulatory agenda, to be dropped the second that addressing debanking might result in consumer protection requirements forcing companies like his to treat customers properly.

This disconnect between rhetoric and reality matters because it threatens to derail meaningful progress on debanking. Real victims of discriminatory banking practices — racial and religious minorities, low-income individuals, legal but controversial businesses — need systemic solutions and stronger consumer protections. Glimmers of bipartisan agreement emerged during the hearings — with various Congresspeople and witnesses describing potential changes to improve transparency or appeals processes when banks deny services to prospective customers. However, in the end, the Congressional majority appears far more eager to spend its political capital making bold statements about debanking only when it applies to crypto billionaires, while dismantling the very agencies best positioned to help debanking victims.

The path forward requires separating legitimate concerns about discriminatory debanking from the crypto industry's self-serving narrative. It requires acknowledging that proper oversight of high-risk industries isn't the same as improper targeting of vulnerable groups. Most importantly, it requires maintaining and strengthening — not dismantling — the regulatory frameworks that protect consumers from both discriminatory banking practices and predatory financial schemes.

I have disclosures for my work and writing pertaining to cryptocurrencies.

Footnotes

As I was writing this piece, Adam Levitin at Credit Slips published a piece entitled “Debanked by the Market”, going into much more detail about this very thing. Highly recommend. ↩

This was another comment echoed by witness Mike Ring, who seemed concerned about the possibility that his Old Glory Bank might end up having to provide banking to Planned Parenthood. ↩

Witness Aaron Klein, Senior Fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution, noted later on (and in his written testimony) that this was a very flawed characterization, as banks routinely cause people to overdraft their accounts when they might not otherwise, including through shady tactics such as reordering transactions so that withdrawals hit before deposits. ↩

References

“Why Banks Are Suddenly Closing Down Customer Accounts”, The New York Times. ↩

“Omar, Warren, Lawmakers Seek Information from Big Banks on Account Closure Practices that Discriminate Against Muslim Americans”, 2023 press release by Ilhan Omar. ↩

“People of Color and Low-Income Communities Are Disproportionately Harmed by Banking and Financial Exclusion”, 2022 report by Democrats on the Joint Economic Committee. ↩

“DeSantis signs bill targeting banks and creating IRS liaison for Floridians”, Tampa Bay Times. ↩

“15 AGs put BofA on notice for ‘de-banking’ conservatives”, Banking Dive. ↩

“Which US Senators Have Signed Their Names to the SAFER Banking Act of 2023?”, Cannabis Business Times. ↩

“Notification of Engaging in Crypto-Related Activities”, FDIC. ↩

February 5, 2025 FDIC Records—Correspondence Related to Crypto-Related Activities, p. 536. ↩

February 5, 2025 FDIC Records, p. 790. ↩

February 5, 2025 FDIC Records, p. 651. ↩

February 5, 2025 FDIC Records, p. 520. ↩

February 5, 2025 FDIC Records, pp. 494–495. ↩

February 5, 2025 FDIC Records, pp. 503–504. ↩

February 5, 2025 FDIC Records, p. 599. ↩

February 5, 2025 FDIC Records, pp. 516–517. ↩

February 5, 2025 FDIC Records, p. 462. ↩

“Powell Vows to Cut Fed Manual Language Amid Debanking Concerns”, Bloomberg. ↩

“Last-Gasp Trump Rule May Force Banks to Lend to Gun Companies”, The Trace. ↩

Senator Tillis speaking at the “Investigating the Impacts of Debanking in America” hearing, 59:26. ↩

“Ricketts Leads Opposition to Marijuana Banking Bill That ‘Facilitates Money Laundering for Drug Cartels’”, Senator Pete Ricketts. ↩

Senator Ricketts speaking at the “Investigating the Impacts of Debanking in America” hearing, 1:50:10. ↩

“Two top CFPB officials resign after being ordered to stop all work”, NPR. ↩

“Analysis of CFPB consumer complaints related to debanking”, supplemental memorandum filed by Elizabeth Warren. ↩

“Supreme Court sides with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, spurning a conservative attack”, AP News. ↩