I am my own legal department: the promise and peril of “just go independent”

Independent publishing is one important facet of the media ecosystem, and while I love it, I know it is not the path for everyone.

When a major legacy news publication does something controversial, I sometimes hear my name. “Just go independent! Do what Molly White does.” You’ve probably seen it too: advice to staff writers to “just go independent” like Heather Cox Richardson, or Casey Newton, or those guys over at 404 Media. “Just do a Substack! It’s the future of journalism.”

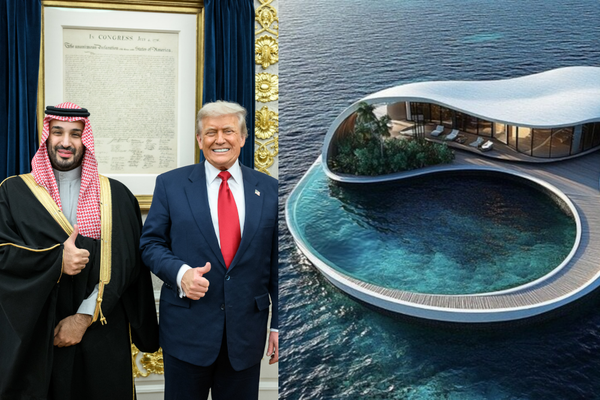

When news broke yesterday that Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos had spiked the newspaper’s planned endorsement of Kamala Harris, editor-at-large Robert Kagan resigned. Similar events transpired earlier this week at the Los Angeles Times, whose own billionaire owner nixed a Harris endorsement, prompting the resignation of the editor who drafted it. As staff members at those publications and elsewhere spoke out about their frustration and fury at the decisions by those who control their employers’ purse strings, the familiar refrain began. “Why don’t you just quit too? Just go independent.”

The day before the Washington Post news broke, bleary-eyed at 7am as I scanned through my email inbox before getting out of bed to make some coffee, a subject line caught my eye: “DMCA Takedown Notice”.

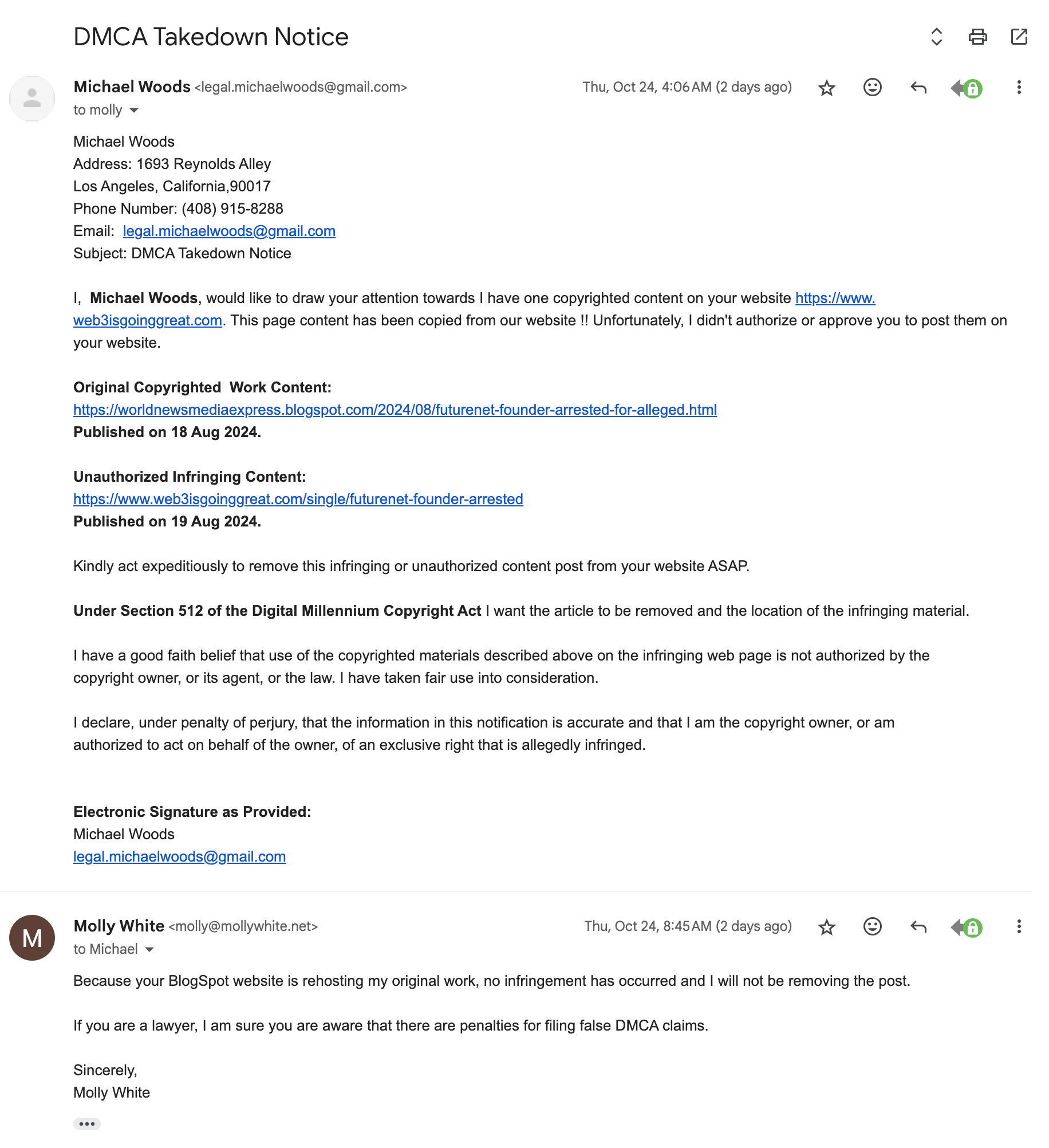

When I went to bed the night before, the plan for the next morning had been to fix a bug in my new presidential election spending tracker in Follow the Crypto, a page I urgently wanted to release as Election Day looms here in the United States. Now I knew those plans would have to wait until after I finished cosplaying as a lawyer, figuring out if and how to respond to some guy who’d — as far as I can tell — been hired by the alleged operator of a multi-million dollar cryptocurrency pyramid scheme to file a fraudulent copyright claim in an attempt to force me to take down a Web3 is Going Just Great post I’d already refused to delete.

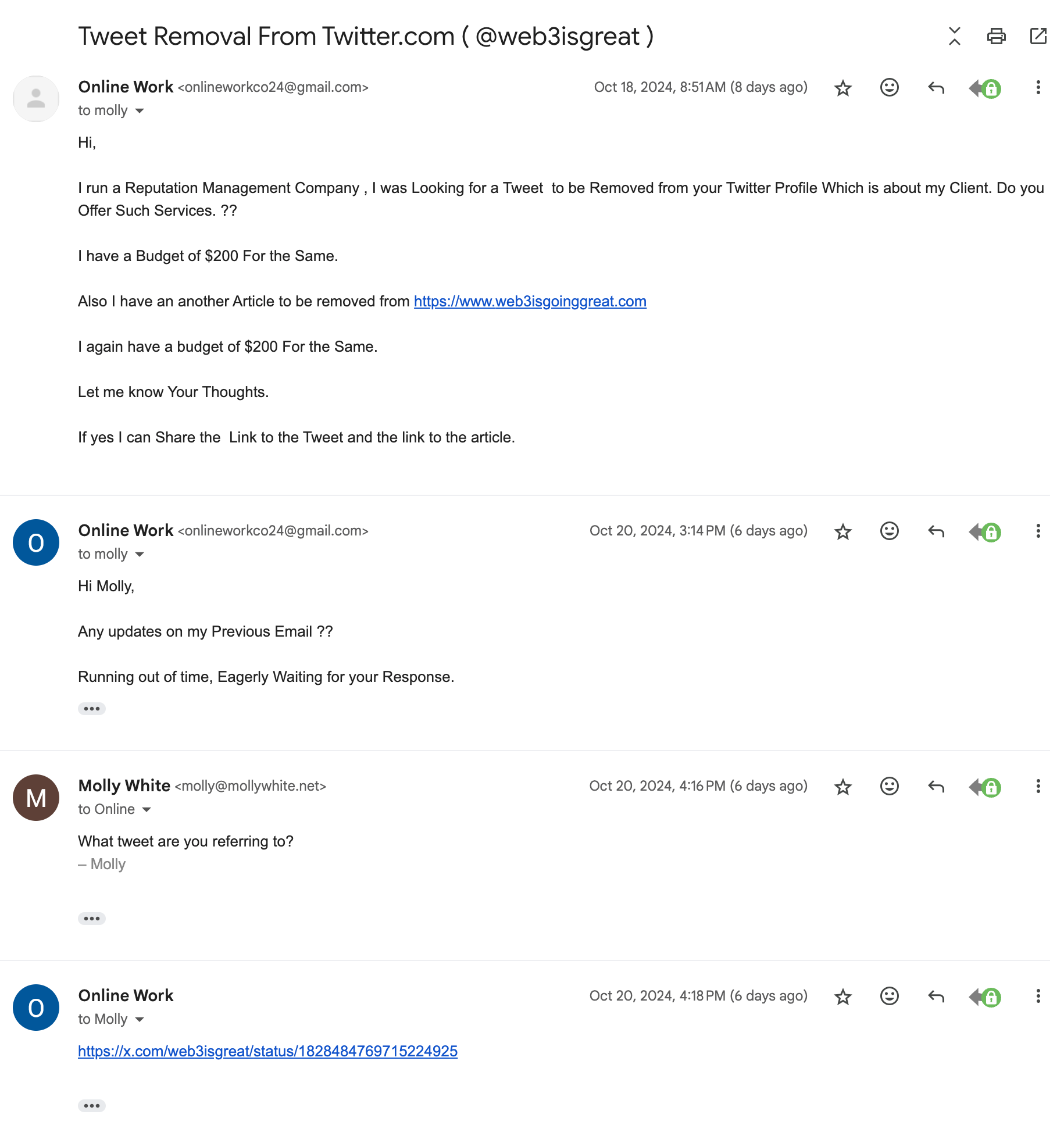

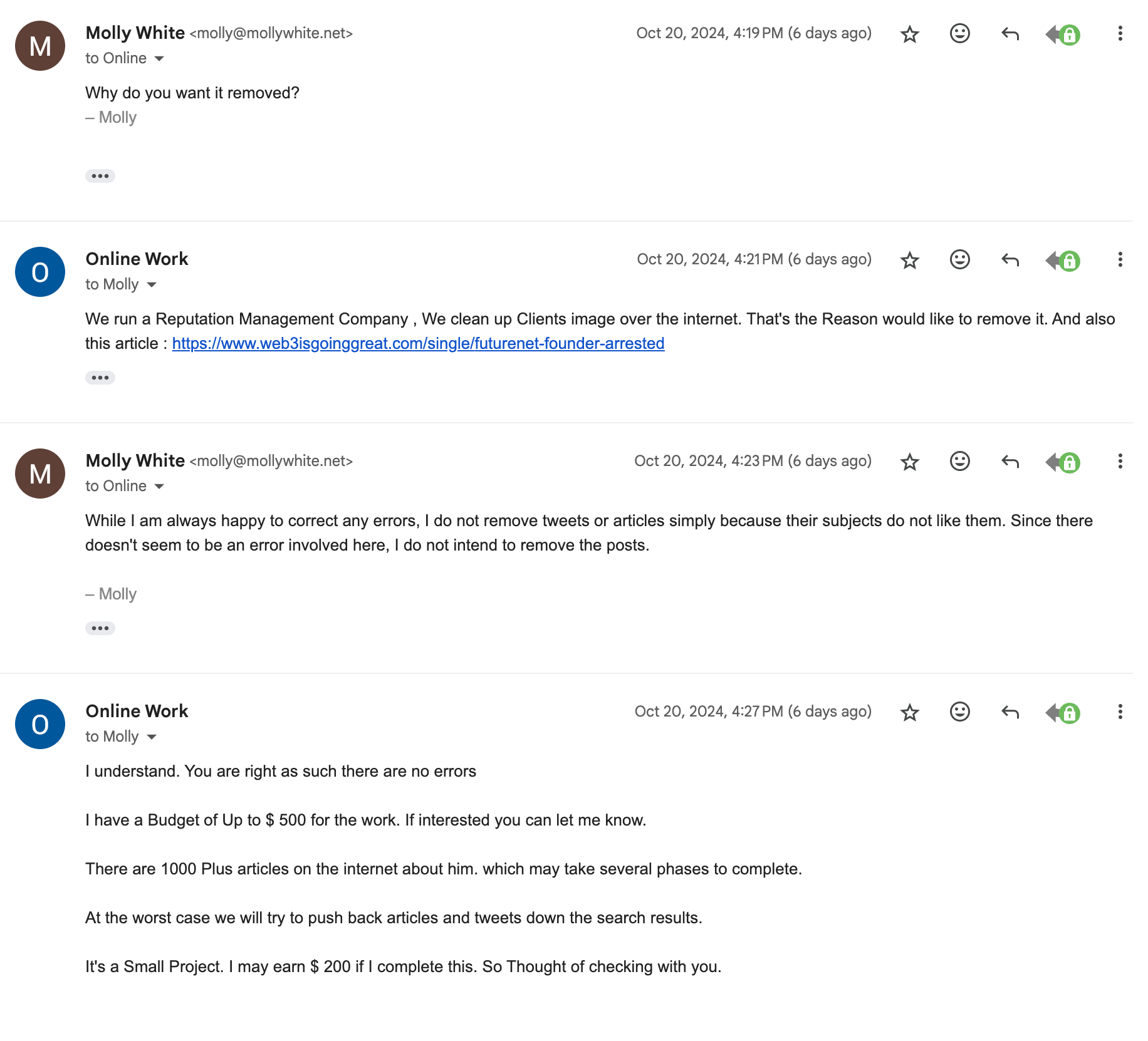

A week prior, I’d received an email from an amateurish “reputation management company” offering me $200 each to delete the story and the associated tweet. I replied to inform them that, while I’m always happy to correct any errors, I do not remove posts simply because their subjects don’t like them. “I understand. You are right as such there are no errors,” they replied, then upped their bribe to $500. I stopped responding, and assumed that was that.

Instead, either the client or the “reputation management company” decided to try a new tactic. Following a familiar playbook, they copied my Web3 is Going Great post to a free BlogSpot website, then backdated it by one day.a The goal was to then abuse the notice and takedown process to claim that I had stolen their work, force my webhost to remove the post, and then hope that I was either intimidated by the legalese or too strapped for time to fight it out with my hosting provider.b Unfortunately for them, “legal department” is only one of the many hats I wear as an independent writer and publisher, and “hosting provider” is another. I informed them that no such infringement had occurred, and noted that there can be penalties for fraudulent copyright claims should they try to continue pursuing this tactic. I hope this is where they give up, and my legal department that contains no actual lawyers will have sufficed this time, as it has several other times in the past.

Had I been a journalist at an outlet like the Post, this likely would never have required any of my time at all. Outlets like that have teams of actual lawyers who are in charge of handling copyright complaints. They also vet journalists’ stories to ensure they are carefully written so as to minimize the chances of defamation lawsuits, and defend the publication and its journalists from any claims that come in anyway. They handle all of the many other types of legal concerns that impact journalists and publishers.

As an independent writer and publisher, I am the legal team. I am the fact-checking department. I am the editorial staff. I am the one responsible for triple-checking every single statement I make in the type of original reporting that I know carries a serious risk of baseless but ruinously expensive litigation regularly used to silence journalists, critics, and whistleblowers. I am the one deciding if that risk is worth taking, or if I should just shut up and write about something less risky. I am the one who ultimately could be financially ruined by such a lawsuit. I am the one in charge of weighing whether I should spring for the type of insurance that is standard fare for big outlets to protect themselves and their staff, but often prohibitively expensive for independent writers. I am the one putting on even more hats: risk manager, insurance broker, business consultant, CPA.

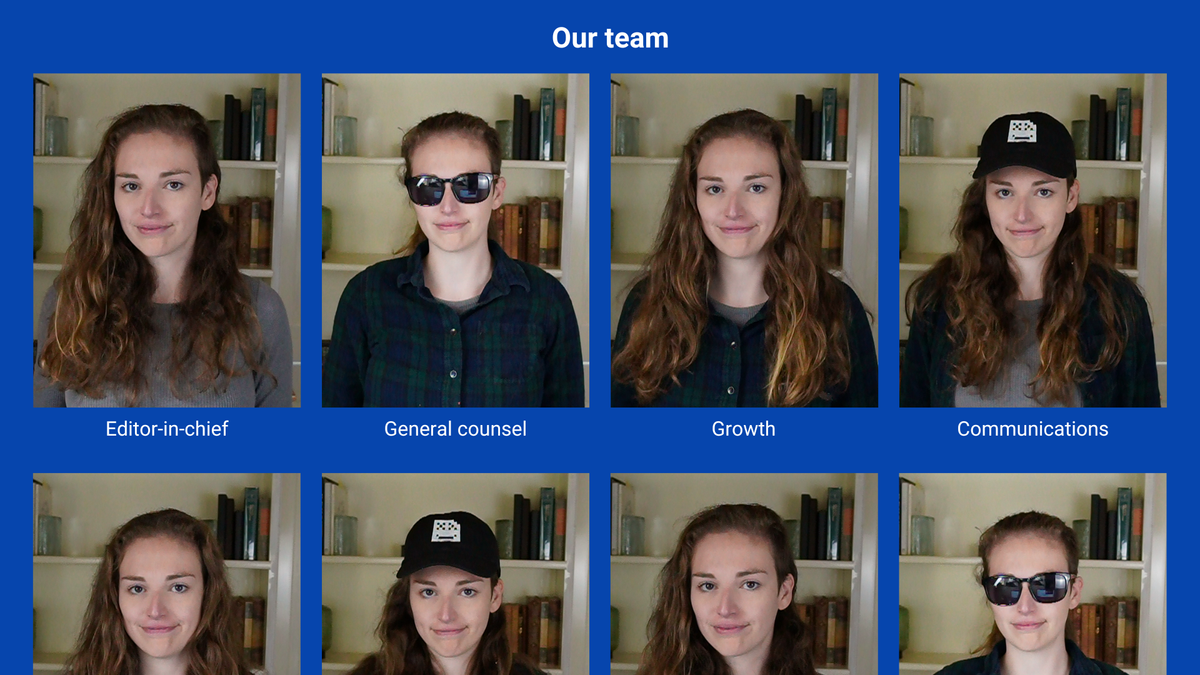

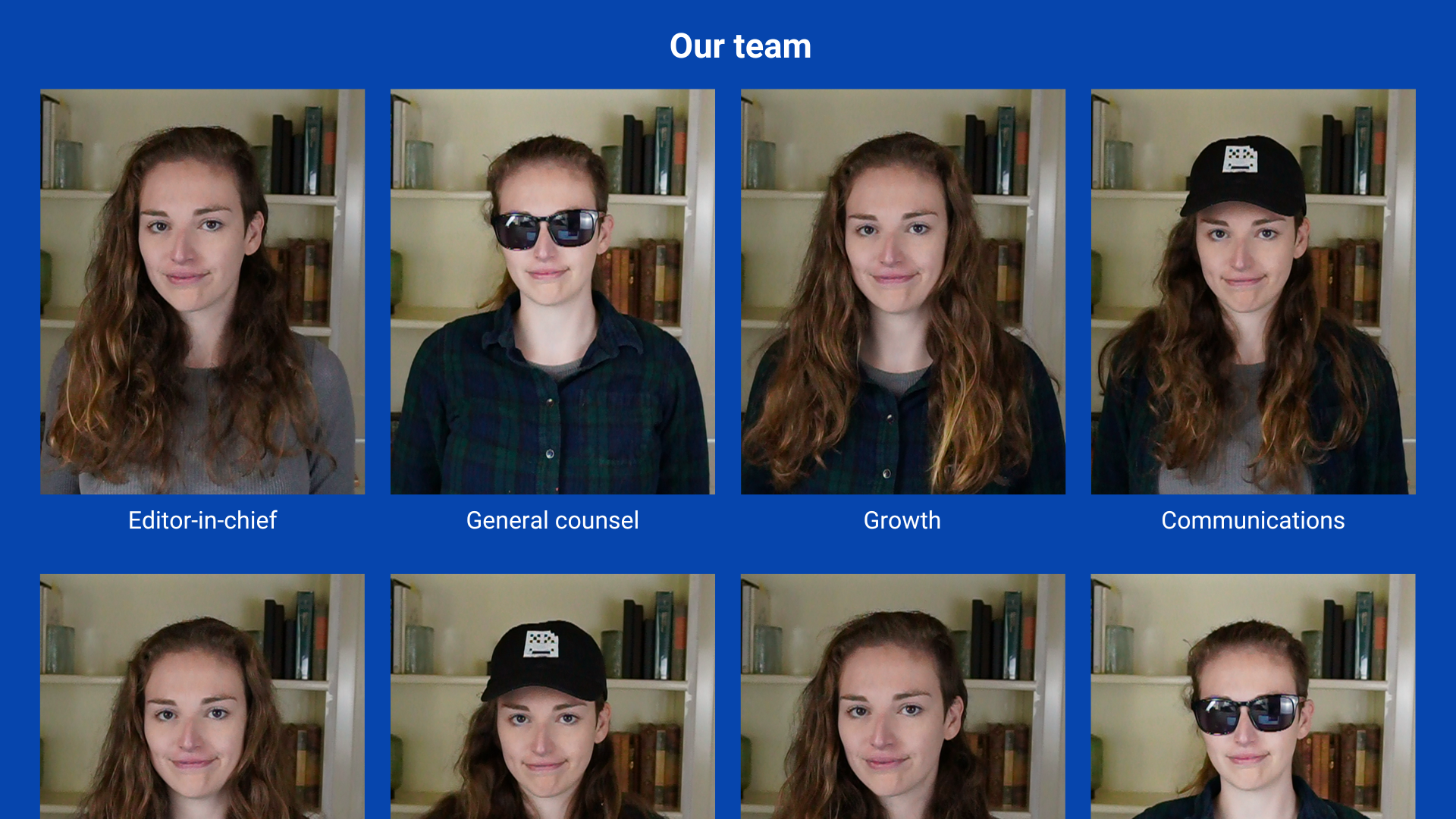

Occasionally I am reminded that many don’t realize that independent publications like mine are often a one-man band: one person wearing many disguises. When I published my recent interview with Ryan Salame, I laughed when I saw a comment on social media: “Your photo editor captured the spirit of the piece pretty well.” I get comments like this a lot, more often when I make a mistake. “Whoever edits your audio versions accidentally left in a retake.” It’s me, hi, I’m the problem, it’s me.

It’s not a silly assumption to make; after all, some independent writers do bring on outside help by hiring editors or research assistants or social media managers. It’s a wise move, and maybe someday I will too. Maybe.

But for now, Citation Needed is just one person with a tall stack of hats. The research team? Me, poring over FEC filings or the deluge of PACER alerts from dozens of court cases, so that I can be the one who first notices that Ryan Salame has formally declared his innocence after pleading guilty, or that Marc Andreessen has donated another $2 million to Donald Trump. The software department? Me, writing custom code so that people get emails informing them that their subscriptions are about to renew. The social media team? Me, crossposting across at least four different platforms because social media, despite its fragmentation, is still an important way to reach people and, though I hate it more than anything, urge people to toss a couple of bucks my way so that I can keep doing this mad work. I am the customer support department when emails go missing, the sysadmin when the website is slow, the accountant who chews her fingernails over monthly recurring revenue graphs as the group of people who signed up for annual subscriptions during my Sam Bankman-Fried trial coverage decide whether or not to renew. Recently, I am the merch department who designs and packs envelopes full of stickers, and in many cases I’m the manufacturer of the stickers, too.

And I would have it no other way. Perhaps I thrive in chaos more than I realize, and the unpredictability of waking up every day not knowing if I’m going to write a blog post or talk to a Senator or learn how to edit video helps to keep things interesting.

But I also truly control my own destiny this way, for better and for worse.

I don’t worry that I will be next on the chopping block as my legacy media organization performs yet another wave of layoffs. I don’t worry that others at my publication will publish work that completely contradicts my values. I don’t worry that my employer will try to control what opinions I express on social media, or that any of the many people who don’t like my opinions will succeed in getting me fired for having them. If something I publish triggers a massive wave of subscribers to cancel, well, I was the one who wrote it. And when I see a spike in subscriptions because something I wrote really resonated with people, that joy is my own. When I read comments from people who thoughtfully engage with my writing — whether to agree or disagree — I know that they’re leaving those comments because I have cultivated a space where we can respectfully discuss our opinions and where people know I read every single comment.

I don’t fear that my entire publication will be forced to kowtow to the whims of billionaire trying to make nice with a fascist. I don’t fear that an editor will tell me I can’t publish an article calling Donald Trump a fascist. I don’t have to get anyone to approve it when I say that I, and Citation Needed, wholeheartedly endorse Kamala Harris for president, not because she is perfect but because the other option is violent authoritarianism. I know that this risks backlash from those who don’t support Harris, or perhaps from those who don’t think this newsletter should be a place for politics, but I also know that by now, readers should know I hold strong opinions and always speak my mind.

But where I may be immune from the threat of layoffs or getting fired for a tweet, there are different fears. The abject terror of “what if this totally flops and I can’t pay my bills?” has diminished somewhat now that I’ve been writing Citation Needed for over two years, at least, but the constant background anxiety that people will lose interest in what I write about, get burned out on the email newsletter format, or stop being able to even find my writing because of the ever-shifting web discovery and social media landscape will always be there. It’s a strong motivation to always be improving and trying new things, but it is also exhausting.

While I love it, I know this life is not for everyone. Some people just want to write, and recoil at the idea of also being in charge of every other aspect of running a business.c Some people want to do the kind of journalism that truly requires a whole support staff. Some people have personal circumstances where they simply can’t make the choice to have unpredictable income, no employer-sponsored health insurance, or no 401(k).

Any truly healthy ecosystem must be diverse, and that holds true for media. Independent writers and publishers — be it one-man bands like myself, or small teams — are a crucial part of this ecosystem, but we cannot be the only part. It should be a mix that also includes larger publications at local, national, and international levels. Importantly, this mix of publications needs diversity in funding models as well. Some have argued that “subscriptions are the future of news!”, and they might be surprised to hear that, as a subscription-funded writer myself,d I disagree. The subscription model is one model that works well, but it is not without its flaws, including a tendency to push content behind paywalls and out of reach of those who can’t afford it, and a tendency to overwhelm people who want to read a wide range of writers but who cannot afford dozens of subscriptions. Rather than searching for the One True Funding Model for News, a mix of funding models strengthens the whole ecosystem.

For many, “just go independent” is not feasible advice. It should not be the default advice for any journalist who complains about issues at their publication, when instead these publications could be changed to better support their journalists and to better serve their readers.

But for some, it is a worthwhile and enormously rewarding choice. If anyone out there is thinking about pursuing it, I am an open book. After all: the price of independence may be high, but the cost of silence is even greater.

Footnotes

Whoever was behind this scheme apparently did not catch on to the fact that Web3 is Going Just Great posts are dated based on the day the event occurs, not the date I publish them, and so their backdated post about Roman Ziemian’s arrest was supposedly published the day before Ziemian’s arrest was announced by Montenegrin authorities. ↩

For better or for worse, the notice and takedown process is slanted in favor of the complainant. If a person simply states that they are the copyright holder and they have a good faith belief that a site has infringed upon their copyright, hosting providers will typically remove the content as a first resort, and then give the site owner an opportunity to argue the claim. ↩

In fact, I distinctly recall telling someone years ago that I would never start a business, but here we are. It’s only recently that I’ve come to the realization that what I do can be called a “business”, silly though that might sound. ↩

One could also reasonably describe me as operating on a donation model, given that these subscriptions are optional and pay-what-you-want. ↩