Not just one bad apple: FTX's practices were business as usual in crypto

Adversary cases from the FTX collapse further expose how crypto companies do business: with secret acquisitions of “grey area” businesses, buying influence, and creative accounting.

Over a year after Sam Bankman-Fried’s trial, perhaps one of the most memorable moments to stick with me was an unexpected one: a brief exchange between prosecutors and BlockFi founder Zac Prince. (FTX’s collapse bankrupted the crypto lender, which had loaned FTX entities hundreds of millions.)

BlockFi's Zac Prince: [With] crypto firms, it was much less common to have audited balance sheets because of issues with getting audits as a cryptocurrency firm.

Prosecutor: Just to be clear, some of the balance sheets you received from crypto firms were what is called unaudited balance sheets.

Prince: I would say the majority of balance sheets that we received from cryptocurrency firms were unaudited.

This casual statement about lending hundreds of millions based on scrawled estimates and a “trust me, bro” underscored the deception in crypto executives’ post-collapse claims that FTX was a rare bad actor with aberrant business practices, a black sheep among scores of legitimate businesses. On the contrary, many of FTX’s activities were business as usual in an industry where regulatory enforcement and proper audits were rare, but maximal leverage and risk-taking were par for the course.

I’m not so much fascinated by the specifics of the FTX adversary cases two years post-bankruptcy, where the debtors work to claw back the remaining traces of FTX’s exorbitant spending. Instead, I’m interested in the pulling back of the curtain on the cryptocurrency industry’s day-to-day operations. Shady practices have become so commonplace as to be open secrets, only questioned during occasional brushes with those from more strictly regulated financial sectors — who often react with horror when given a peek at the crypto industry’s standard operating procedure.

In the span of only a few days in November 2024, the FTX bankruptcy estate filed over thirty adversary cases.1 Several target political action committees and non-profits that received hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars from FTX as part of the company’s political influence campaigns and reputation polishing efforts. Others target other cryptocurrency exchanges where Alameda Research or affiliated entities were trading — sometimes secretly — and where account balances haven’t been released back to the bankruptcy estate. Some target FTX customers engaged in criminal behavior. And some target employees, contractors, or business associates of FTX and its entities.

Genesis Block

In early 2020, FTX entities acquired Hong Kong-based Genesis Block, an over-the-counter trading firm and cryptocurrency ATM operator. It served as a crypto on- and off-ramp in Asia, where the company publicly acknowledged they were operating in a “grey area”. “People were literally lining up around the corner with bags of cash at Genesis Block,” a former employee said. “Sometimes they shut the door saying they were out of bitcoin.” The company was a valuable asset for FTX, allowing them to circumvent capital controls and providing business connections in Asia.

FTX’s ownership of Genesis Block was kept secret from the public and from regulators. FTX also used Genesis Block to make venture investments and operate various other entities they acquired or created in Singapore, the Philippines, and Mexico, so as to reduce regulatory exposure. (FTX employees helpfully put their reasoning in writing). While FTX was still in Hong Kong, Genesis Block was the nominal employer of several FTX personnel — including Gary Wang and Nishad Singh — in order to circumvent visa requirements.

Genesis Block co-founder Clement Ip has rather brazenly claimed he is owed $65.8 million held in an FTX account belonging to his partner’s company, Myth Success. However, FTX debtors say Myth Success was yet another shell company used by FTX to circumvent regulators, acquire companies without publicizing FTX’s involvement, and secretly trade on other platforms, and that it had no business operations of its own. As FTX collapsed, when its executives were desperately searching the couch cushions for money to satisfy withdrawals, Genesis Block and Myth Success acknowledged that the money in Myth Success’s accounts belonged to FTX, and transferred some of it back. However, the debtors allege that “Ip appears to have hoped that the fact of these transfers would be lost in the chaos and disarray of the FTX Group’s implosion”, and described his claim on the assets as “a baffling act of hubris”.

The Genesis Block adversary case also finally explains the many references to “our Korean friend” in the FTX trial. This nickname was used for the internal FTX account that hid Alameda’s billions in liabilities, opened in the name seoyuncharles88@gmail.com. Throughout the trial, there was infuriatingly little indication as to who this person was. Liz Lopatto wrote:

[Adam Yedida] wasn’t even doing anything shady like transferring money from Alameda’s account to the “Korean friend” account. (I still don’t know what the deal is with the username “seoyuncharles88” and I am starting to get kind of pissed that no one is explaining it.)

It turns out that the “seoyuncharles88” FTX account was registered to Yang Jai Sung, father of Genesis Block’s head trader, Charles Yang, and opened using his passport and bank statement. An internal note when the account was opened stated, “[A]lameda [was] gonna use this for deposits withdrawals.” Later, according to Gary Wang’s testimony, Alameda’s negative balance on FTX would be moved to appear under the seoyuncharles88 account, “so that its balances would not be included in the line-of-credit interest payments that Alameda was paying.” It appears that the account was never under Yang Jai Sung’s control, but was instead a name used internally to obscure FTX’s fraud in its own records.

Criminal activity on FTX

Some adversary cases involve FTX customers allegedly engaged in criminal activity.

The MobileCoin exploiter

In my November 2023 article “The stones left unturned in the Sam Bankman-Fried trial”, I expressed frustration with one of the many loose threads from the FTX criminal trial: a trader who stole around $800 million by exploiting flaws in FTX’s risk management software.

What we haven't learned is who this customer was, or why they were so valuable that Bankman-Fried thought it was worthwhile to avoid liquidating them even when facing a threat of an exploit that could — and did — cost the company almost its entire annual revenue for that year. There has also been no evidence that FTX ever tried to recoup the funds via legal action against the customer, whose identity should presumably have been known to FTX as a part of their standard know-your-customer process (which Bankman-Fried also described in his testimony). Why not?

We now have a little more information from an adversary case filed against Nawaaz Mohammad Meerun, previously known as “the MobileCoin exploiter”. It turns out that Meerun, a Mauritian citizen, is a rather prolific cryptocurrency scammer, and is the very same “Humpy the Whale” behind governance attacks on protocols including Compound Finance [W3IGG], Balancer, and SushiSwap. He also, according to the debtors, “has been linked to money laundering operations and Ponzi schemes dating back more than a decade, and has extensive ties to Polish, Romanian, and Ukrainian organized crime networks, including groups linked to human trafficking, as well as to Islamic extremist networks linked to terrorist financing.”

The negligence and incompetence at FTX when it came to Meerun suggests that it is truly miraculous that more exploits of this nature didn’t occur. An outside company had to alert FTX to Meerun’s activities, and even then, FTX did almost nothing to stop him from accumulating massive positions in illiquid tokens that would later cost the company hundreds of millions. Instead, FTX executives said it “would be cool to keep him as a friend though since he’s like 50% of our margin platform lol” — even as Meerun opened new accounts to bypass the limited restrictions FTX did put in place. And although you might think FTX’s know-your-customer system would help them identify all of these accounts he was opening, Meerun exposed that the KYC processes were clearly intended only to provide plausible deniability that the company was complying with regulations, rather than to allow FTX to definitively establish account operators’ identities. Meerun had no trouble using fake identification to open accounts (occasionally even reusing the same documents across multiple accounts or photoshopping IDs with the same photos), and using fictional addresses and even nonexistent area codes. Several accounts were accessed from the same devices, and Meerun almost seemed to taunt FTX by using silly and distinctive food-themed email addresses like “kingofthepudding” and “donerkebabveryspicy”.

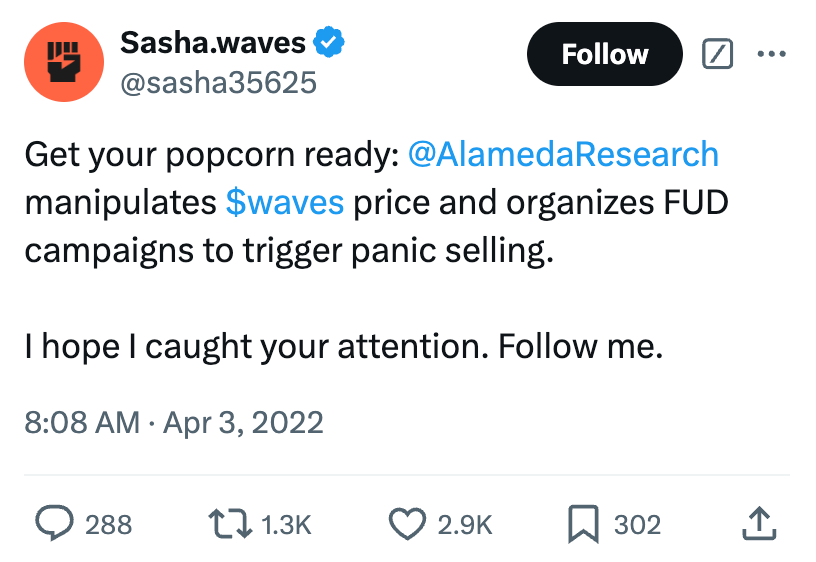

Sasha Ivanov, Waves, and Vires

Another shady operator on FTX was Aleksandr “Sasha” Ivanov, founder of the Waves protocol and Vires lending platform. In March 2022, Alameda Research decided to deposit around $80 million into the project, which boasted quite literally unbelievable yields of 30–70% APY. As is often the case with projects boasting of such high yields, it turned out that Ivanov was allegedly inflating the WAVES token price to siphon $530 million from users [W3IGG].a When things began to unravel, and the Waves stablecoin began to lose its peg [W3IGG], Ivanov blamed Alameda Research:

Despite smearing their company on Twitter, Ivanov was reportedly trying behind the scenes to get Alameda to publicly announce their earlier $80 million investment into Waves, hoping that the endorsement of such a then-influential player in the crypto world might stabilize the rapidly deteriorating situation. Ivanov threatened that if they didn’t, the Vires DAO would liquidate Alameda’s position.b When Alameda refused, the DAO passed a proposal to limit stablecoin withdrawals to $1,000 a day, ostensibly to prevent “bots” from draining the project. This change meant Alameda would need over 200 years to withdraw their assets, $1,000 at a time. Later, the project forced users to convert their USDC and USDT (Tether) stablecoin positions to USDN — a “stablecoin” which by that point routinely fell below its supposed $1 peg, and which would later collapse entirely.

When FTX and its related entities collapsed, the projects refused to return Alameda’s money to the bankruptcy estate — despite Ivanov’s public statements that Alameda’s funds on Vires “could help to repay those users affected by what is being called the worst collapse in crypto history”. Ivanov then dissolved the legal entities operating Waves and Vires, and falsely claimed that the debtors had failed to respond to his communications.

Chinese money laundering ring

The third adversary case against FTX customers allegedly involved in criminal activity differs from the other two in that the criminal activity wasn’t directly targeting FTX entities. Instead, the bankruptcy estate is trying to reclaim funds from an “international criminal syndicate” that allegedly laundered billions of dollars in criminal proceeds via FTX. The case names 24 defendants, plus “John Does 1–20” (representing accounts opened under fake names or stolen identities), which FTX says were Chinese nationals operating a money laundering ring. While the case doesn’t detail the money’s origin, it definitely wasn’t from their day jobs — one defendant, a schoolteacher, deposited over $581 million into his FTX account.

In September 2022, FTX’s compliance team noticed a link between the accounts and questioned group members about the source of the funds. The members all told the compliance team that the money was coming from various other members, many of whom were family. It’s unclear if FTX reported the incident to law enforcement, although the debtors do note that a team of law enforcement investigators contacted FTX to request information on the same group in October 2022. FTX closed the members’ accounts on November 3, 2022 — days before FTX collapsed.

Binance

One of the most notable of the adversary cases is the one against Binance, which helped push FTX into its full-on collapse and was (briefly) also its last hope of survival.

The FTX bankruptcy team is digging all the way back to July 2021, when Sam Bankman-Fried bought back Binance’s stake in FTX. To recap, Binance had purchased a 20% stake in the then fledgling company in late 2019, but the relationship between the two companies soured as they became competitors. As Sam Bankman-Fried told it,2 when FTX was seeking regulatory approval in Gibraltar, and was thus required to provide details about its major shareholders, Binance’s reluctance to divulge necessary information to regulators prompted Bankman-Fried to buy back Binance’s stake in the company. However, according to both Binance CEO Changpeng “CZ” Zhao and the recent lawsuit by FTX debtors, it was Zhao who initiated the buyback due to “personal grievances he had against Bankman-Fried”. Regardless of who started it, Bankman-Fried eventually forked over around $1.76 billion in Binance’s BNB token and BUSD stablecoin, and in FTX’s native FTT token.

Now, the FTX bankruptcy team is arguing that FTX and associated companies “may have been insolvent from inception and certainly were balance-sheet insolvent by early 2021” and, as such, the transfer was fraudulent. They also tack on claims of injurious falsehood,c fraud, intentional misrepresentation, and unjust enrichment against Binance and Zhao, claiming that Zhao’s “campaign to destroy FTX” ruined shareholder value. This “campaign” refers to Zhao possibly being the one to leak the balance sheet showing Alameda’s precarious finances, tweeting about offloading Binance’s FTT holdings, allegedly doing so in a way that would most dramatically hurt the FTT price, and offering to acquire FTX then rescinding the offer very shortly after. While it seems pretty uncontroversial to say that Zhao was hoping to sink FTX with these actions, these portions of the complaint seem like kind of a stretch. Zhao’s behavior certainly didn’t help matters, but it was FTX’s insolvency caused by massive fraud that caused customer losses, and it seems unlikely Zhao could’ve ruined the company with tweets alone if everything been on the up-and-up. Binance has not yet filed a response to the lawsuit.

Alameda’s trading activities

Some adversary cases seek to claw back funds that FTX entities held on external cryptocurrency exchanges where Alameda Research and other subsidiaries traded. It’s somewhat remarkable how many exchanges have just flat-out refused to return the funds, despite bankruptcy laws requiring it.

Some cases seem simple, where exchanges refused to return assets in accounts opened under Alameda Research’s name: the debtors claim that MEXC is holding assets priced at $6 million as of FTX’s bankruptcy date, and that South Korean exchange KuCoin is hanging on to $30 million.

Some cases are made more complex because Alameda Research was trying to hide its trading activities on those outside platforms by using accounts in the names of its employees or associates. $53.4 million in assets, for example, are stuck on the Upbit exchange in an account opened, again, in the name of the father of Genesis Block trader Charles Yang.

Some refusals to return funds may stem from FTX and other exchanges being locked in a standoff, with frozen funds on each other’s platforms. An Alameda account on Gate.io opened under Gary Wang’s name contains around $30 million, after debtors regained around $10 million of the balance. However, Gate.io in turn has a claim against FTX for $13.3 million.d An Alameda account at Crypto.com under the name Ka Yu Tin, the CFO of Genesis Block, holds $11.4 million. This case is complicated by Crypto.com’s claims against FTX totaling around $18.6 million from Crypto.com and its co-founders.

Finally, an adversary case against the Justin Sun-owned Huobi (now HTX) and Poloniex exchanges alleges that they are improperly holding on to a combined $27.5 million. Though both accounts belonged to Alameda Research, the Huobi account was opened in a former employee’s name, and the Poloniex account was nominally registered to Sam Bankman-Fried. A Huobi subsidiary also withdrew around $14 million from an FTX account in the preference period prior to its collapse, which FTX is trying to claw back, and various Justin Sun-affiliated entities have filed roughly $30 million in claims on assets held at FTX.

The Justin Sun entities’ refusal to return assets are shrouded in the same sort of suspiciousness that tends to follow Sun everywhere he goes, and the excuses provided to the FTX debtors are troubling. First, a member of Huobi’s legal team member told the FTX bankruptcy team he didn’t work at the “correct” Huobi entity, and refused to identify which entity this was, or provide details for anyone who worked there. Then Huobi claimed Chinese police were investigating the Alameda-owned accounts on Huobi, but refused to provide any further information. At Poloniex, employees made “seemingly arbitrary” requests for the debtors, then claimed that Poloniex was undergoing an “internal restructuring” and cut communications.

Personally, if I were on the FTX bankruptcy team seeking to regain access to funds held on Justin Sun-owned platforms, I’d be very concerned about whether the money was there at all.3

Cronyism

Several of the adversary cases reveal the extent to which FTX’s lavish spending benefited friends and associates of its top brass. It’s no shock that a company funneling tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in commingled company and customer funds to its top executives for real estate and other luxuries was doing so elsewhere, but the absolute uselessness of that spending was almost impressive.

For example, FTX spent $25 million to acquire Good Luck Games, a company which just so happened to have been founded by Sam Bankman-Fried’s childhood friend and godbrother Matthew Nass (along with several others). All the company had to show for it was Storybook Brawl, a prototype of an auto battler game whose only claim to fame was that Bankman-Fried was publicly a fan, often playing the game during business meetings (and, later, during public Q&A sessions during the media tour where he tried to establish an innocent explanation for his company’s collapse).

The game never left beta, and it shut down only a few months after FTX’s collapse (though not before Nass tried to buy back the rights to the game for a piddling $1.4 million). According to the debtors, “the speed with which [Nass and his co-founders] were unjustly enriched was, indeed, comical.” Their employees — some related to GLG’s founders — were understandably excited to receive bonuses as high as almost $200,000 in a single month, with one remarking “Fucking sick these bonuses lol. Amazing.” Nass agreed that it was “so fun being santa” (with FTX’s customers’ money).

Neil Patel, a search engine optimization and digital marketing guru, also landed a $30.8 million windfall thanks to his “years’-long pre-existing relationship with a top in-house lawyer at the FTX Group.”e Although Patel and his company NP Digital were expected to work on marketing for FTX, the work was allegedly horrendous — or nonexistent. According to the debtors, Patel was paid $14.8 million “to spend four months merely attempting to find another consultant, which it never actually did.” Patel also allegedly double-charged for his work across multiple FTX entities, and even submitted (and was paid) invoices after being fired. Some contracts he negotiated with FTX were kept secret from other employees, which the debtors surmise related to potential discontent if employees found out that the guy who produced work they described as “sooo sloppy” and having “terrible performance” was being paid millions.

Political contributions

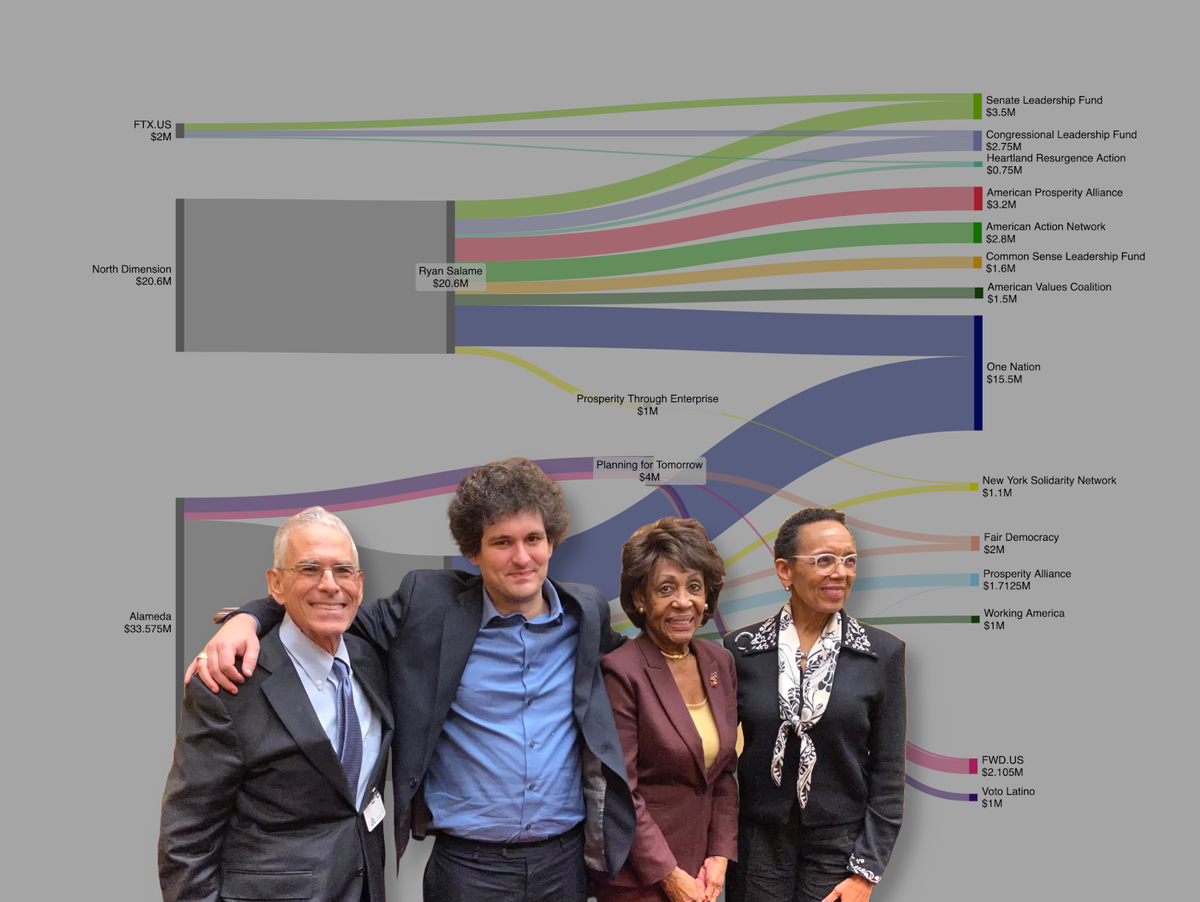

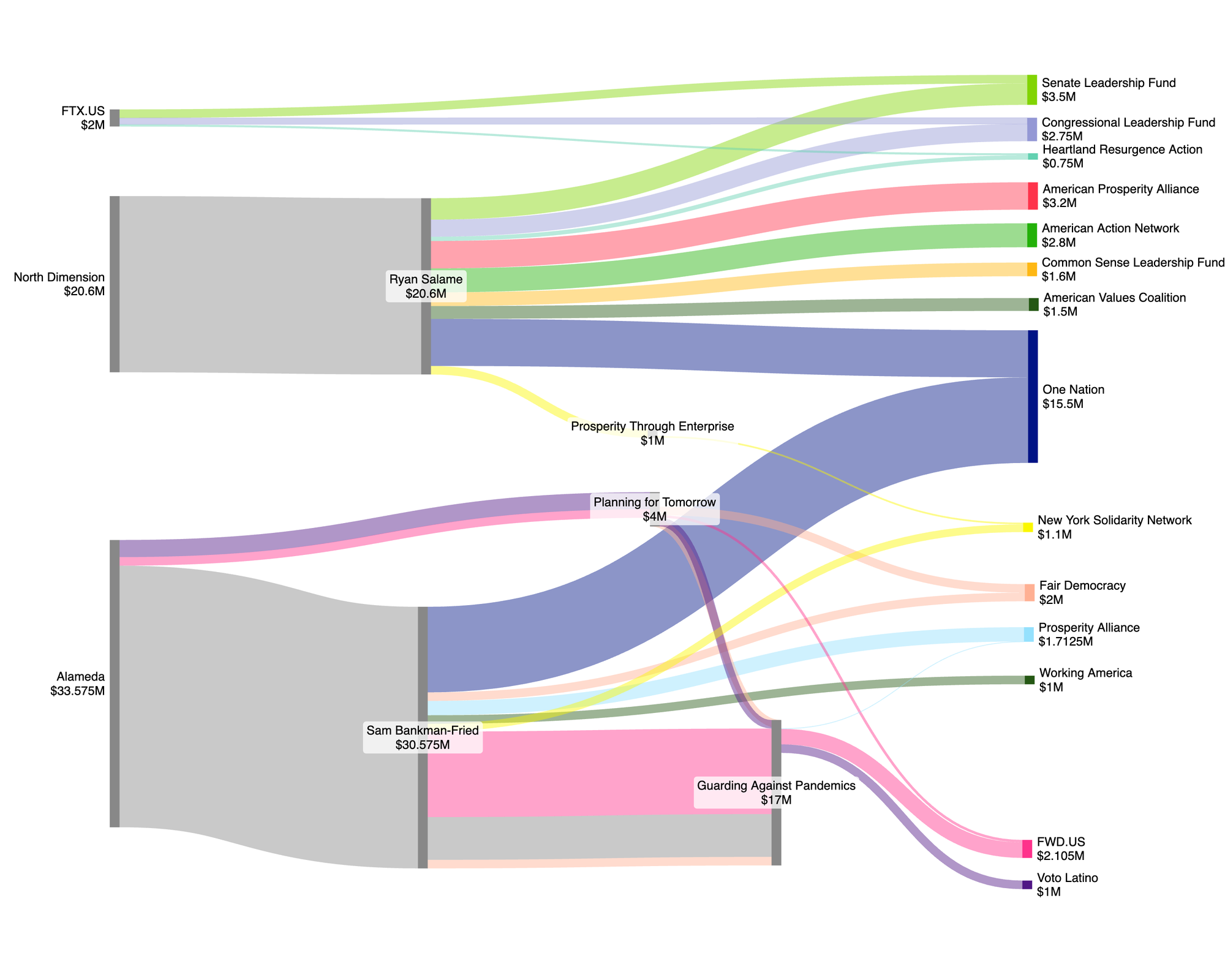

In the year or so prior to FTX’s collapse, Sam Bankman-Fried undertook a political strategy that became the template for the industry-wide influence campaign in 2024. He spent heavily across political parties (though some of these contributions were concealed, as Bankman-Fried tried to maintain a progressive image) to both install favored candidates and buy favors. He met with Congresspeople to pitch specific proposals he had crafted for cryptocurrency industry regulation. He backed a crypto-focused super PAC called GMI (short for “gonna make it”), founded by FTX’s Ryan Salame, which pulled in over $10 million from FTX executives, Andreessen Horowitz’s co-founders, and other crypto industry figures. The PAC pushed for legislation to remove cryptocurrency tokens from the Securities and Exchange Commission’s authority.f

The efforts were nakedly transactional, buying access and influence for Bankman-Fried, his political right-hand man, Ryan Salame, and political operatives like his brother, Gabe Bankman-Fried. A spreadsheet maintained by Gabe’s Guarding Against Pandemics super PAC (which was “almost entirely funded—if not entirely funded—by Sam Bankman-Fried”, and was used to conceal millions of dollars in FTX-funded political contributions) boasted that “several dozen candidates” backed across both parties “are in congress and owe us favors”.

After FTX’s collapse, some recipients sheepishly returned the money, embarrassed to be associated with the uncovered fraud. Others kept or had already spent it, and have been targeted with adversary cases seeking to claw back the contributions. In these cases, we gain insight into the tangled web of money transfers behind many of these contributions, as the commingled FTX company and customer funds were transferred between FTX entities, executives, and various outside connected groups to obscure the true source.

These include:

- $15.5 million to One Nation, a 501(c)(4)g that has contributed heavily to Republicans and conservative causes, including efforts to restrict anti-racism curricula in schools and abortion access. The contributions were routed through Ryan Salame and Sam Bankman-Fried.

- $3.5 million to the Senate Leadership Fund, a super PAC supporting Senate Republicans. Some money was routed via Ryan Salame, while some was contributed directly by FTX.US.

- $3.2 million to the American Prosperity Alliance, a 501(c)(4) that serves as a primary arm of the Koch brothers’ libertarian political influence. These contributions were routed through Ryan Salame.

- $2.8 million to the American Action Network, a conservative 501(c)(4) “action tank” that has in the past worked to oppose the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Green New Deal, and the Affordable Care Act. These contributions were routed through Ryan Salame.

- $2.75 million to the Congressional Leadership Fund, a super PAC supporting House Republicans. Some money was routed via Ryan Salame, while some came directly from FTX.US.

- $2 million to Fair Democracy, a 501(c)(4) supporting Democratic candidates, voter education, and engagement. These contributions were routed via Sam Bankman-Fried, Guarding Against Pandemics, and Planning for Tomorrow.h

- $1.8 million to FWD.US, a 501(c)(4) founded by Mark Zuckerberg claiming to support criminal justice and immigration reform. These contributions were routed via Sam Bankman-Fried, Planning for Tomorrow, and Guarding Against Pandemics.

- $1.6 million to the Common Sense Leadership Fund, a conservative 501(c)(4) supporting deregulation and lower taxes. These contributions were routed via Ryan Salame.

- $1.5 million to the American Values Coalition, an evangelical Christian non-profit claiming to “reject extremism and misinformation”. These contributions were routed via Ryan Salame.

- $1.17 million to Prosperity Alliance,i a 501(c)(4) supporting Republicans and conservative causes, mainly focused on the economy. These contributions were routed via Sam Bankman-Fried, with some going directly to Prosperity Alliance from him, while the rest was routed first through Guarding Against Pandemics.

- $1.1 million to the New York Solidarity Network, a 501(c)(4) for pro-Israel efforts. The contributions were routed through Sam Bankman-Fried and Ryan Salame, with Salame’s funds also detouring through Prosperity Through Enterprisej before going to the NYSN.

- $1 million to Working America, a 501(c)(5) labor organization claiming to “empower workers who do not belong to labor unions”. This contribution was routed through Sam Bankman-Fried.

- $1 million to Voto Latino, a 501(c)(4) “focused on educating and empowering a new generation of Latinx voters, as well as creating a more robust and inclusive democracy”. The contribution was routed through Planning for Tomorrow and Guarding Against Pandemics.

- $750,000 to Heartland Resurgence Action, a conservative 501(c)(4) funded by agriculture executives. Some money was routed via Ryan Salame, while some was contributed directly by FTX.US.

Again, these were only a portion of all the political donations made by FTX and its affiliates. Another nine political organizations not named here have just returned a combined $14 million as a result of settlements with the bankruptcy estate.4

Charitable contributions

Sam Bankman-Fried and FTX also spent heavily on ostensibly charitable causes, most of which were related to the effective altruism movement, and which seemed more designed to enrich those working on those projects. As an overtly EA-aligned organization, Bankman-Fried was diligent about his and his company’s austere image, downplaying his personal spending and highlighting his personal and corporate philanthropy. In one case, according to the adversary case against Ryan Salame, Bankman-Fried had Salame purchase a $15.9 million private jet for him and the company — something Bankman-Fried considered an “extremely sensitive topic” not to be mentioned due to “concern about PR”.

As boilerplate in the philanthropy-related adversary cases puts it:

FTX Philanthropy claimed on its website that it “works to save lives, prevent suffering and help build a flourishing future.” In reality, very few of FTX Philanthropy’s donations directly benefitted the needy. Its largest donations went to associates of FTX Insiders in the “effective altruism” movement…

The adversary cases against philanthropic groups reveal the extent to which these funds were outright wasted on enriching Bankman-Fried’s personal friends without ever reaching the vulnerable people Bankman-Fried claimed to have devoted his life to helping.

For example, FTX contributed around $570,000 to a non-profit called Nonlinear, founded by effective altruists Emerson Spartz and Kat Woods.k The group had “formed relationships with FTX Insiders” and were invited to the Bahamas to visit. Although the corporation was ostensibly focused on streamlining charity grantmaking, it seems to have since pivoted to “AI safety”.

Another $750,000 went to a newly created company, On Ten Productions, which planned to make a documentary film on the origins of the COVID-19 virus. The debtors state that no film was ever created, although in 2024 On Ten did release a 90-minute film on the COVID-19 lab leak hypothesis titled Spiked: The Hunt For The Origin Of Covid-19.

Another $1.2 million went to a non-profit effective altruist-led pandemic prevention organization called SecureBio; $680,000 went to The Goodly Institute to “build AI decision-making tools for human utilization”, and $508,000 went to Manifold Markets to fund their “charity markets” — a program where the fake money used in their betting markets could be converted to real money for effective altruist causes.

Other shady business

The last remaining adversary cases are tough to categorize, but exemplify the shady business that is an everyday part of operations in the crypto world.

The Mooch

FTX is trying to recover over $100 million from transactions with entities associated with Anthony Scaramucci, who I’ll note is still, more than seven years later, earning snarky comments in legal filings over his ten-day “brief stint as a White House Communications Director”. The adversary case aims to regain funds transferred to Scaramucci’s SkyBridge investment funds and related conference series. FTX’s investments in SkyBridge’s crypto funds made no financial sense, with employees questioning why an experienced crypto trading firm like Alameda Research would spend $45 million to obtain interest in “a basket of cryptocurrencies that the FTX Group could have easily purchased itself less expensively”, purchased by an investment fund with little crypto trading experience, worth about $12 million.

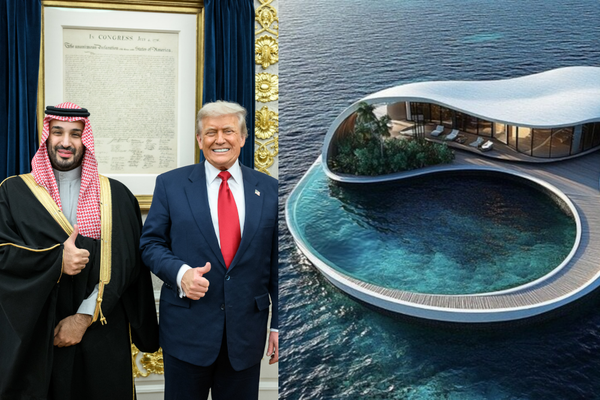

The money was plainly intended to buy access to Scaramucci’s network of celebrities and investors, and Scaramucci is portrayed in the adversary case as far more of a shrewd networker than he is a capable investor. Both Scaramucci and Bankman-Fried are depicted by the debtors as mercenary: Scaramucci allegedly cultivated the relationship with Bankman-Fried out of desperation over his rapidly failing crypto fund, hoping he was someone who would “spend money while asking very few questions”. Bankman-Fried, realizing that the FTX entities were in a dangerous position after spending so much of his customers’ money, was eyeing Scaramucci as a connection to wealthy investors who might provide an eventual bailout and, thus, cover up his fraud. Both were ultimately correct: Bankman-Fried poured millions into Scaramucci’s lackluster crypto funds on “highly unfavorable terms” in what “was, for all intents and purposes, a bailout of SkyBridge”, while Scaramucci took Bankman-Fried on an influence tour with “major financiers, former White House officials, and Middle Eastern heads of state,” including Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The adversary case, though it is only a civil matter seeking to recover funds from Scaramucci, seems to accuse the influential investor and his business partner of serious wrongdoing. According to the debtors, “Scaramucci and his partner, Defendant Brett Messing, both managers of SkyBridge II, ignored the bargained-for restrictions on Skybridge’s ability to sell the tokens and raided Plaintiffs’ segregated cryptocurrency account no later than December 2023. ... By late 2023, it became apparent that Scaramucci and Messing at best grossly mismanaged SkyBridge’s assets and, at worst, may have looted the assets for themselves.” The debtors add that, despite the fund’s poor performance, Scaramucci and Messing paid themselves over $22 million — more than the fund brought in in management fees. Amidst all this, Scaramucci has just announced he’s buying a new Lamborghini.5

Farmington State Bank

Another entry in my “Stones Left Unturned” piece dealt with FTX’s acquisition of Farmington State Bank (later renamed to Moonstone Bank), a deeply weird moment in FTX history when Alameda Research spent $11.5 million — twice the tiny rural bank’s entire reported net worth — to obtain a 10% stake in the business. The bank had just been acquired by Jean Chalopin, chairman of the Bahamas-based Deltec Bank and Trust (a key bank for both Alameda Research and Tether), and Moonstone quickly began to brazenly violate its agreed-upon regulatory restrictions when it suddenly tried to pivot to becoming a crypto bank.

Unfortunately, the adversary case seeking to claw back this money doesn’t shed much more light on what the hell was going on here, other than to vaguely mention that FTX entities “opened bank accounts with Moonstone to facilitate a $50 million tax safe-harbor required by a transaction with another U.S. company”.

Silver Miller

A case against Florida law firm Silver Miller seeks the return of some or all of nearly $2 million they were paid, mostly in the form of a monthly retainer paid in exchange for “minimal legal work”. An internal document revealed that FTX tracked law firms filing class action suits against cryptocurrency companies, and the self-described “cryptocurrency loss & investment fraud”-focused team of lawyers at Silver Miller was among them — apparently because they had brought a complaint against Binance on behalf of a customer whose holdings on the Kraken exchange were stolen and transferred to an account at Binance.6 (The case would go on to be dismissed a year later due to lack of jurisdiction over the Cayman Islands-registered Binance.)

In order to “conflict out” the law firm — that is, to introduce a conflict of interest to prevent Silver Miller from litigating against FTX — FTX signed a contract to engage Silver Miller for $70,000 a month for 24 months. The pricey contract brought on Silver Miller in exchange for little more than an explicit agreement not to bring action that would conflict with FTX’s interests for a period of five years. According to the debtors, “From May to September 2022, Silver Miller provided one piece of known work product regarding FTX US’s Terms of Service, and provided occasional, high-level counsel regarding a few isolated issues.”

Ryan Salame

Unsurprisingly, the bankruptcy estate hopes to claw back assets from FTX executive Ryan Salame, though whether he has much left after his substantial criminal restitution is certainly an open question. According to the debtors, Salame received nearly $100 million in misappropriated funds. Most of the adversary case rehashes what we already know about Salame’s role in FTX, which I’ve outlined in Issue 59 and my interview with him just before he reported to prison.

However, the adversary case does outline some additional details that cast further doubt on Salame’s claims of being an innocent victim coerced to plead guilty to crimes he didn’t commit. When describing Salame’s role in opening bank accounts for an FTX shell company — contributing to his charge of conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transmitting business — the debtors note that Salame appears to have deleted messages from a Slack conversation with a bank manager to try to cover his tracks.

The adversary case also outlines that Salame continued to spend FTX money even after its bankruptcy, including to purchase two condos. One was in a complex in Portugal that advertises that purchasing its units can help a person qualify for Portugal’s “Golden Visa”, a shortcut to obtaining Portuguese residency.

From secretly acquiring “grey area” cash-for-crypto businesses to buying political influence to paying off lawyers, the FTX adversary cases describe incredibly shady practices that are far from as unusual as the crypto industry likes to claim. Remember: all of these activities happened while FTX ran Super Bowl ads about being a “safe and easy way to get into crypto” and Bankman-Fried described his business at every opportunity as “the most regulated crypto exchange by far”.

Troublingly, the conditions that enabled FTX’s fraud remain unchanged today. Lack of auditing is the norm. Knee-jerk resistance to regulation remains the default industry-wide, and the industry refined Bankman-Fried’s early attempts at political influence, spending over $130 million to install handpicked surrogates in Washington to further reduce any chance of meaningful oversight.

With the same red flags waving across today’s cryptocurrency industry, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that similar frauds have only yet to be discovered. The primary difference may be that other firms haven’t faced their CZ moment yet: the pushing over of the first domino that causes the whole precarious thing to collapse.

Footnotes

Amusingly, Ivanov was also facing a separate lawsuit about this from Avi Eisenberg, a crypto trader who was mad that he lost $14.5 million in what he described as Ivanov’s “international Ponzi scheme and bait-and-switch scam”.7 The case was dismissed without prejudice because Eisenberg failed to properly serve the defendants, owing to the fact that he himself was in jail awaiting trial for his own $110 million scam [W3IGG]. ↩

“But Molly,” you ask, “how did Ivanov unilaterally control the DAO, which was supposed to be decentralized?” Like many DAOs, Vires DAO was effectively controlled by the project founder, and was decentralized in name only. ↩

Defamation, but for companies™. ↩

FTX was hardly the only company obscuring its trading by registering accounts under different names. Gate.io’s accounts on FTX were registered to Gate.io CEO Lin Han, as well as two unidentified individuals named Sun Yunzhi and Gao Aizhi. ↩

This lawyer is not identified by name, but my suspicion is that it’s Dan Friedberg. ↩

These bills, the Securities Clarity Act and the Token Taxonomy Act, never made it into law. ↩

501(c)(4)s, also called social welfare organizations, are the most common type of dark money group in the United states. They are not required to disclose their donors, and can contribute to political causes with some vague limitations. ↩

Planning for Tomorrow was a dark money group run by Gabe Bankman-Fried and almost entirely funded by Sam Bankman-Fried. ↩

A different group from the American Prosperity Alliance, despite the similar name. ↩

Prosperity Through Enterprise was a dark money group founded by a close associate of Sam and Gabe Bankman-Fried, Keenan Lantz, who was heavily involved in FTX-related charitable contributions and strategy. Prosperity Through Enterprise was also primarily funded by Sam Bankman-Fried. ↩

Someone named Kat Woods, who appears to be an effective altruist, provided one of the character reference letters submitted by Sam Bankman-Fried’s defense team ahead of his sentencing. In the letter, she claimed, “I’ve never met Sam, but I’ve been harmed immensely by his actions, losing most of what I had.” It’s not clear if this is the same person. ↩

References

Search “adversary” in the docket on the Kroll website. ↩

“Exclusive: Behind FTX's fall, battling billionaires and a failed bid to save crypto”, Reuters. ↩

“Justin Sun is probably insolvent”, Crypto Critics’ Corner. ↩

“FTX debtors recover $14M in political donations”, Cointelegraph. ↩

“How bullish is Anthony Scaramucci? He’s buying a new Lambo as even Democrats embrace crypto”, DL News. ↩

Miro v. Doe, 9:22-cv-80399, (S.D. Fla.) ↩

Complaint filed on July 6, 2022. Document #1 in Eisenberg v. Numeris Ltd. ↩

I have disclosures for my work and writing pertaining to cryptocurrencies.