The FTX trial, day eleven: Off the record

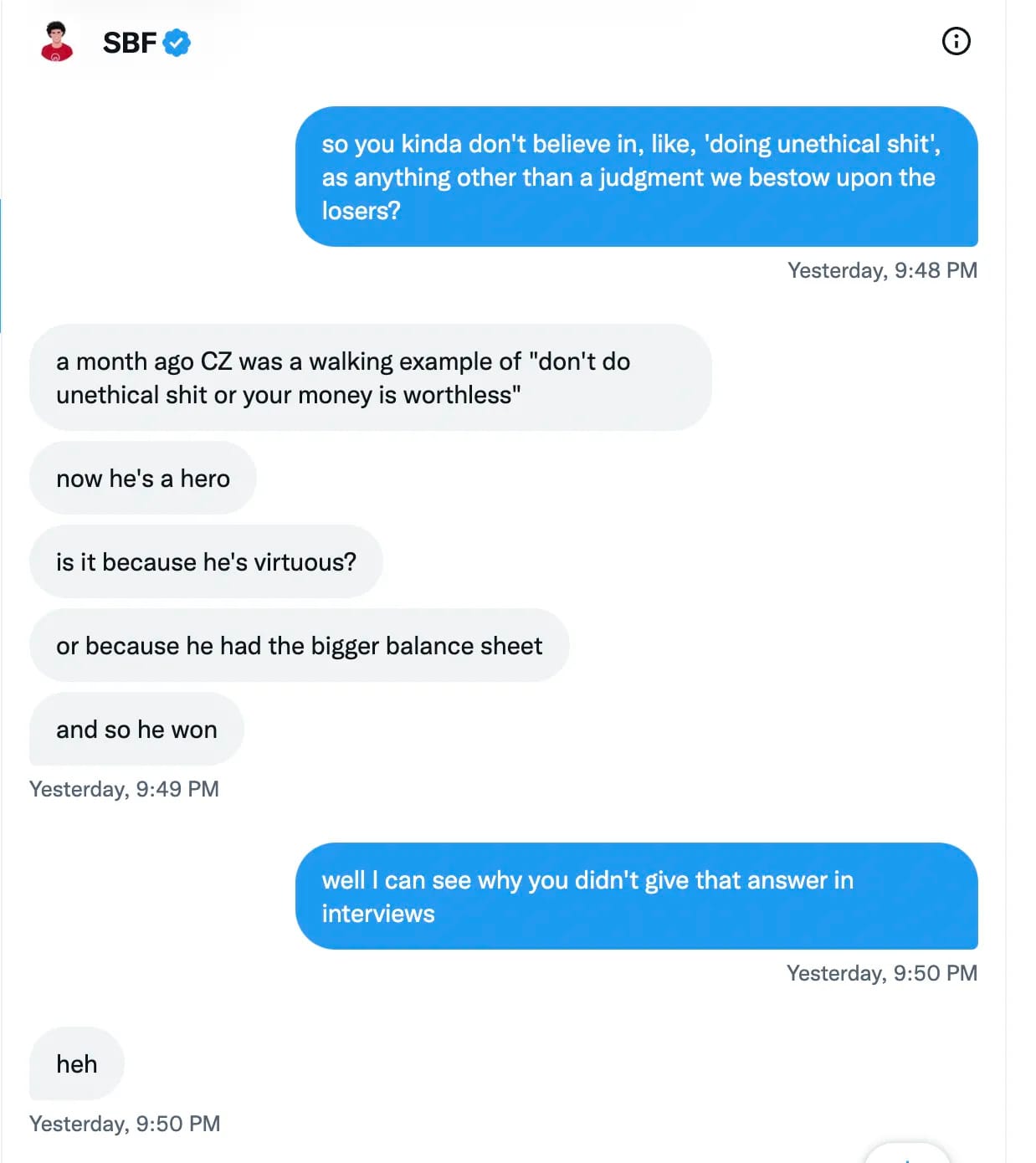

Sam Bankman-Fried's direct messages to a journalist about "unethical shit" were admitted as evidence, much to the dismay of his legal team.

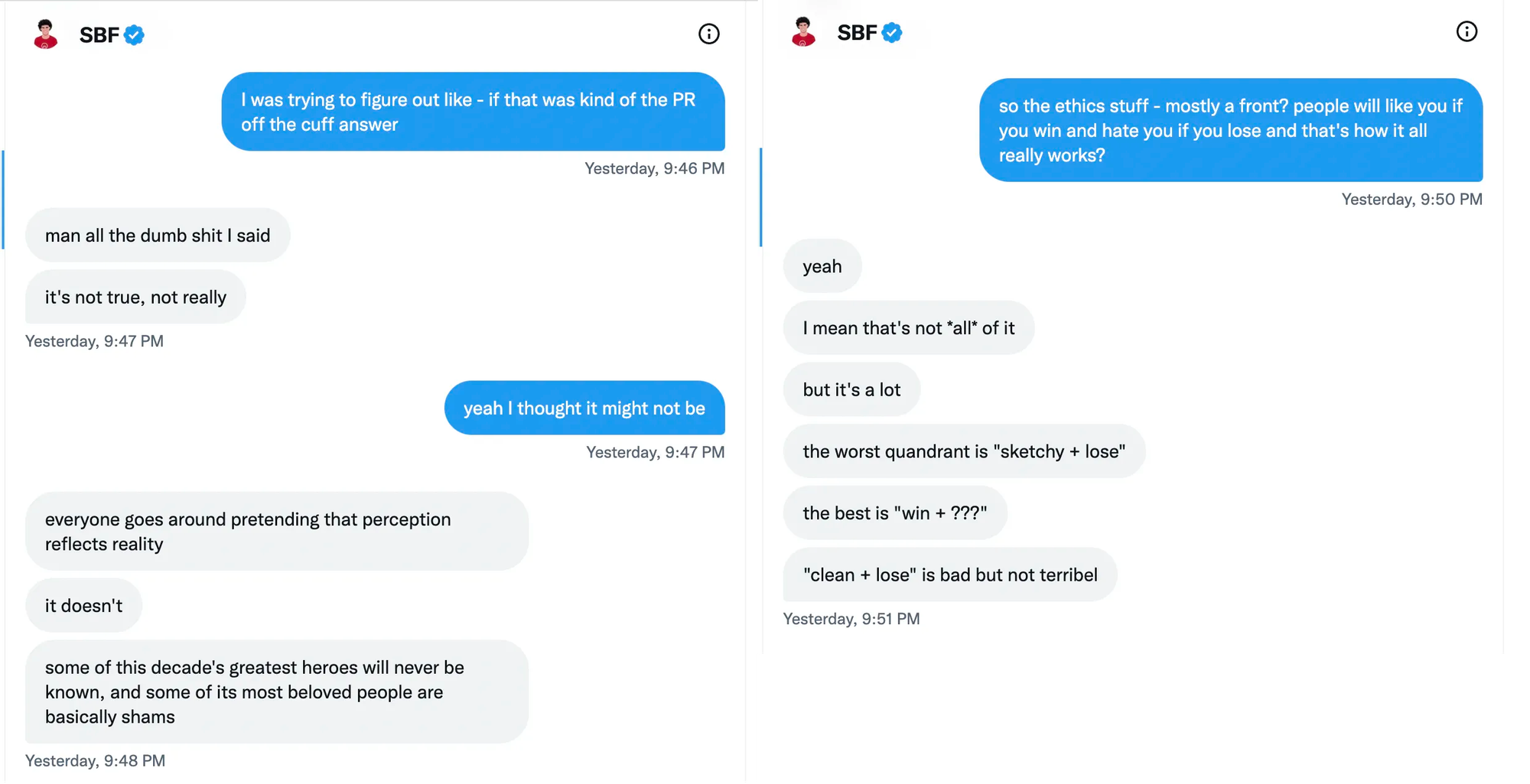

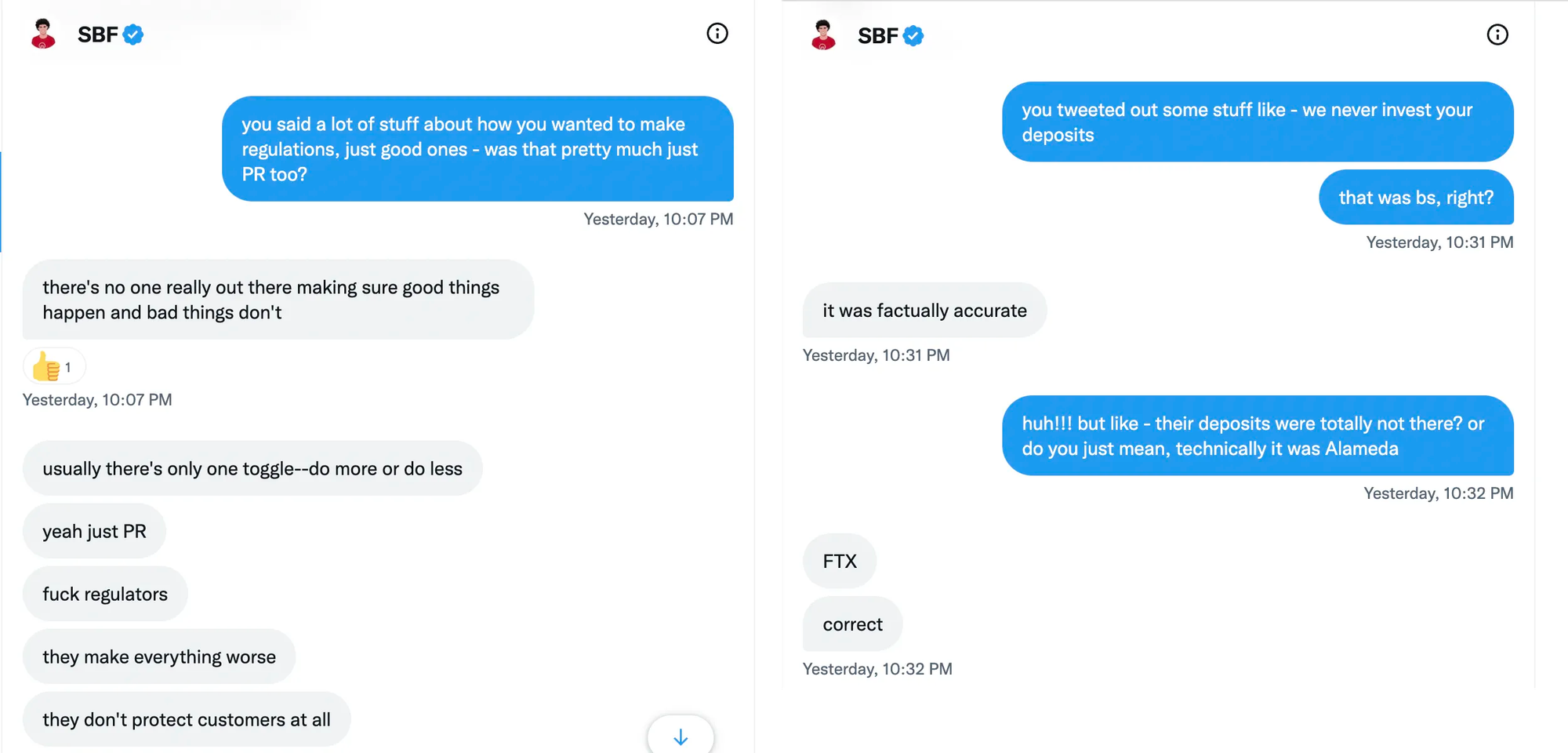

When you're on trial for defrauding the customers of your cryptocurrency exchange, you probably don't want the jury to see evidence of you — only days after its collapse — agreeing that "the ethics stuff" you were so known for was "mostly a front", or admitting that statements that you had made about customer assets were highly misleading even if technically correct, or saying things like "fuck regulators".

That's why Sam Bankman-Fried's attorneys fought like hell on Wednesday to exclude from evidence the Twitter direct messages he'd sent to Vox journalist Kelsey Piper.

Let's back up a little bit.

On November 11, 2022, Bankman-Fried stepped down as the leader of FTX and related companies, turning them over to the control of a team who would lead them through bankruptcy. That was, perhaps, the last rational decision he would make for a while.

Over the following month, he embarked on a vigorous media blitz, talking to just about anyone he could convince to listen. There were a lot of takers. Of course, he appeared for high-profile interviews, such as with Andrew Ross Sorkin at the New York Times' Dealbook Summit or with George Stephanopoulos on Good Morning America, but he would talk to anyone — hell, he even talked to me.

Molly White: Are you worried you might be detained if you stepped foot into the US?

Sam Bankman-Fried: I don't believe I would be, but I haven't done a — like — deep dive into that. At some point, that's something I have to think harder about.

(He was arrested hours later.)

One of the most explosive conversations was one he later said he didn't expect would be made public. Kelsey Piper, a Vox journalist who'd interviewed Bankman-Fried before, decided to take a shot at asking him a few questions. To her surprise, he replied. The following day, she published an article titled "Sam Bankman-Fried tries to explain himself", which largely consisted of screenshots from their chat the previous night.

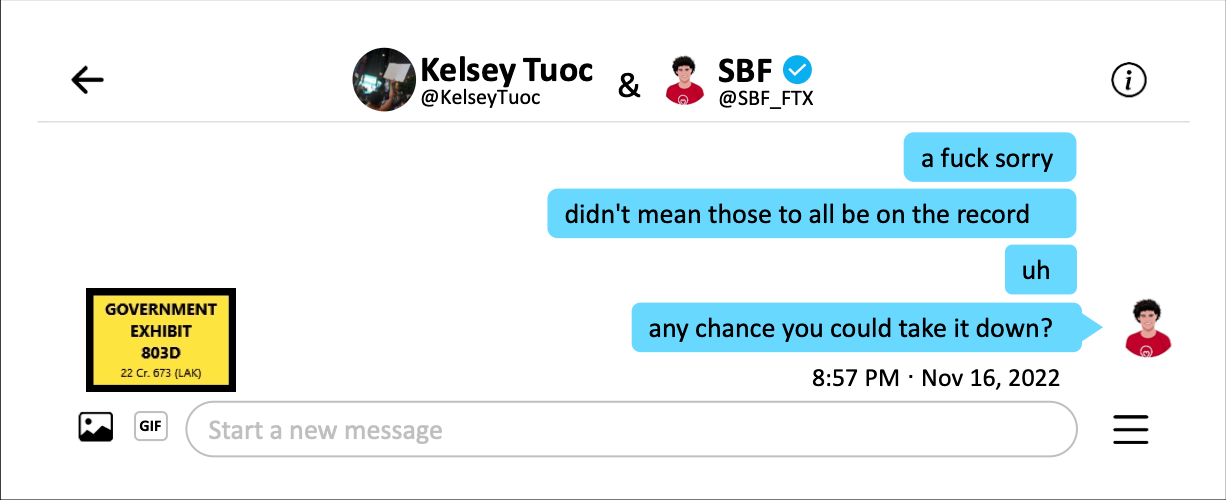

Shortly after she published the article, she received more DMs:

That's not how "off the record" works,a and she did not take down the article. By then it was too late, anyway — the article had quickly blown up, and people who were wondering if maybe FTX's collapse had an innocent, if tragic, explanation now began to realize that Bankman-Fried might have been lying to them all along.

Those chats are now evidence in his criminal case, but it didn't come without a struggle.

At a lunchtime sidebar, Bankman-Fried's defense team objected to them stridently, arguing that they were hearsay, were improperly prejudicial, and were made after the alleged criminal activity had occurred.

Cohen: We think that the probative value is substantially outweighed by the prejudicial effect because these are communications he is making with someone who he knew for a decade, who he considered a friend, and these are just off-the-cuff musings about past events that we think were devoid of context that could be substantially misconstrued by the jury.

It's worth noting that, although Bankman-Fried referred to Piper as "a longtime friend" shortly after she published her article, Piper had a different view of the relationship. A spokesperson for Vox said that, besides their interview a few months earlier, they had only interacted directly a few times several years before that, "through overlapping social and professional networks."

Bankman-Fried's defense team was particularly concerned about the part in which Bankman-Fried spoke about "unethical shit", which they thought was inflammatory and likely to have a prejudicial effect.

Bankman-Fried's defense team also worried about a portion in which he wrote that Nishad Singh was feeling "ashamed and guilty". Mark Cohen said, "It's not in the sense of legal guilt. It's in the sense, I guess, of some sort of personal feelings of guilt. … And because you have the word 'guilt', 'guilty' in this tweet… it's very prejudicial and it is again not very probative of the defendant's state of mind."

The judge helpfully pointed out that if anything was going to bias the jury with respect to Nishad Singh's guilt, it would probably be the fact that he's pleaded guilty to six felony charges.

The defense tried to argue that the government might try to use the part where Bankman-Fried said "fuck regulators" to try to support an argument that "his efforts at engaging with regulators prior to all this was all a sham, which it wasn't." Messages such as these, said the judge, seem like they'd be pretty useful context there.

The government rebutted the defense's claims, arguing that the fact that the statements were made after the alleged crimes was not material: "courts routinely admit post-arrest statements which are after the fact where a defendant is making admissions," argued Assistant US Attorney Danielle Sassoon.

She went on to argue:

The fact here that, as defense counsel said, he's talking to someone he trusted in what he thought was a private context is highly probative that what he's saying here is truthful. The government has offered evidence of the defendant's public representations. This shows the falsity of many of those representations. The fact that it's prejudicial is because it's inculpatory, but that does not make it unfairly prejudicial.

Ultimately, the judge overruled all of the defense's objections to the messages, which were put into evidence and shown to the jury.

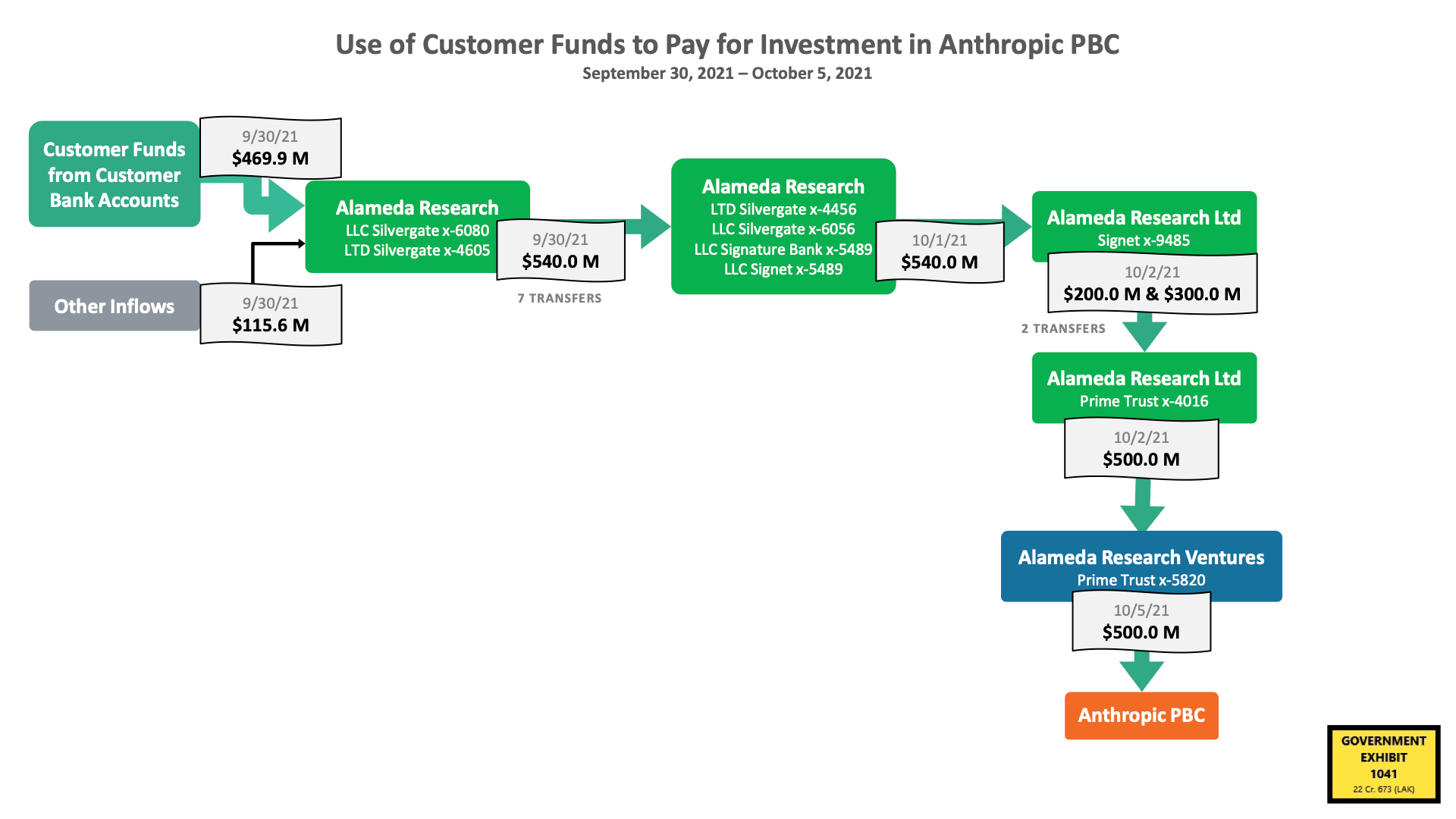

Although testimony from an accounting professor threatened to be dry or difficult to follow, Notre Dame Professor Peter Easton accompanied his explanations with easy-to-follow charts that illustrated the flow of money between FTX and Alameda Research bank accounts, individual people, and expenditures including venture investments, donations, real estate purchases, and various other things.

In some cases, the evidence was clear: payments like a $292 million transfer to invest in Modulo Capital had been made exclusively with customer funds. In other cases, payments were made with a mix of money from trading accounts and from accounts that stored customer funds, but Easton identified dozens of cases in which substantial amounts of customer or investor money was directly used for purposes it shouldn't have been. In one payment, for example, at least $493 million of a $551 million investment in the Genesis Digital Assets crypto mining firm had to have been customer assets.

The professor repeatedly outlined instances in which he traced funds and attributed their sources, to establish the misuse of FTX customer funds and funds from investors to make investments in Skybridge Capital, Dave Inc., and Anthropic; to complete a partnership with K5 Global;b to buy out Binance's stake in FTX; to purchase a stake in Robinhood; to fund political donations by Ryan Salame, Nishad Singh, and Alameda Research; to purchase real estate; and to repay Alameda's loans.

In one example, Easton detailed how the $16.4 million purchase of a Bahamian property for Sam Bankman-Fried's parents came directly out of investor funds. Awkward.

The defense's rebuttal to this line of testimony — as well as to later testimony from FBI forensic accountant Paige Owens — seemed to be that dollars are fungible, and so it was impossible truly to know where a given dollar pooled among other dollars in a bank account went in the end.

This makes sense in some circumstances. For example, say my mom gave me $5 to spend on lunch at school when I was a kid, and I put it in my pocket with another $5 I'd earned by doing an odd job for a neighbor. If later came home from school having spent $5 on lunch and $1 on a candy bar, it would be weird for my mom to get mad at me for having spent the money she gave me for lunch on candy.

The problem is that this argument only works if I already had enough money in my pocket to spend on the other thing. If my pockets were empty and she gave me $5, and I came home hungry and high on sugar because I'd bought a $1 candy bar but no lunch because I only had $4 left, her anger would be much more justified.

In Alameda's case, it was arguably even worse — not only were they taking customer and investor money to spend on things other than what they'd promised, without having sufficient other money in the bank, in many cases they were doing that spending while they also owed money to people. They had negative money in the bank, and they were still blowing money that they shouldn't have even been touching on political donations, real estate, or long-term venture investments.

However, during both Easton's testimony and the later testimony of Paige Owens, the defense found some opportunities to introduce some doubt. In Easton's testimony they seemed to identify an error in one of his exhibits, where he'd improperly included some customer deposits kept at FTX in a graph that was only supposed to show Alameda's liabilities. They also suggested that his analysis might have been incomplete, as it didn't incorporate assets Alameda held on other exchanges, had tied up as collateral for loans, or had put into venture investments. In Owens' case, they questioned her use of LIFO accounting,c suggesting that a FIFOd approach could produce different results. They also revisited one of her exhibits, showing that she might have missed a deposit that ostensibly could have funded one of the political donations by Ryan Salame, instead of customer funds.

Other witnesses today gave relatively little in the way of testimony, but were used to attest that various documents and recordings were authentic (more on that in a minute). Among them was Eliora Katz, FTX US's in-house lobbyist, who was used to introduce to the record written testimony by Bankman-Fried in front of both branches of congress, video clips of his oral testimony to Congress, blog posts about his regulatory recommendations, and various tweets pertaining to crypto regulation (although throughout, she repeatedly emphasized that she did not work at FTX while most of the evidence she testified to was being created).

One clip seemed to show Bankman-Fried rather blatantly lying under oath to Congress in December 2021 that there was "complete transparency" and a "robust, consistent risk framework applied" on FTX:

"We have never had customer losses, clawbacks, or anything like that, even going through periods of large movements in both directions," he boasted.

The prosecution also introduced metadata associated with the various Google Docs and Google Sheets that have been used as evidence throughout their case, which they will presumably use to establish that specific individuals created, edited, or viewed the documents.

Behind the scenes

We got a real taste of Judge Kaplan's frustration on Wednesday, when the Judge instructed both the prosecution and the defense to stay behind during the afternoon break. Several witnesses had been brought in to testify to the authenticity of documents because the two sides couldn't agree to stipulate to them. "Where did he fly in from?" asked the judge, about a Google records custodian brought to testify about metadata, but was not well versed in interpreting it. "Texas," replied the prosecution. "This is a joke," said the judge. "We had a witness this morning, who knew absolutely nothing and spent the time saying 'I had nothing to do with any of that', read documents that are public records. And this afternoon we fly somebody in from Texas to put in documents about what he knows nothing or next to nothing that are obviously stipulatable. We have 18 people devoting time here to this case and it's really a crime, that part of it." He concluded, "Lawyers are supposed to do a little better than this. I am talking to both sides."

Going forward

Tomorrow is the last day in court this week, and it should be a short one. Former FTX attorney Can Sun will testify, as will Third Point managing director Bob Boroujerdi.

After tomorrow, the next day of trial isn't scheduled until the following Thursday, the 26th. I will probably still publish during that break, but with no trial there won't be daily coverage like I've been doing. We could see the beginning of the defense's case as soon as the 26th, assuming they put one on (which they likely will).

Footnotes

Going off the record with journalists is done by mutual agreement, not just because the subject says "I'm off the record", and especially not if they come back and say that after you've already published. ↩

K5 Global is the investment firm co-founded by influence broker Michael Kives. ↩

LIFO stands for "last in, first out", which means that when a bank account receives a deposit, any distributions out of the bank account come from that most recent deposit, and then move backwards from there. ↩

FIFO stands for "first in, first out", which means that the any distributions from a bank account draw from the oldest deposit, and move forwards to more recent ones from there. ↩