Privacy, human rights, and Tornado Cash

I am more worried about privacy than crypto crime.

Alexey Pertsev, one of the developers and operators of the Tornado Cash cryptocurrency mixing service, has been sentenced to 64 months (over five years) in prison in the Netherlands. The service he helped to create enabled criminals to launder billions of dollars in illicit funds connected to massive hacks perpetrated by sophisticated cybercrime groups, ransomware operations that have decimated businesses, and pig butchering schemes that have ruined people. As someone who rails against the abuses by the cryptocurrency industry, why then am I so worried about his conviction, and about the parallel case in the United States against two Tornado Cash co-founders?

Some who know me as a cryptocurrency critic may find these opinions surprising coming from me. But if you are surprised, I have failed. And I think I have, because I think some of you will be.

Tornado Cash and other cryptocurrency mixers generally work by allowing a person to send cryptocurrency in chunks of preset sizesa into a large pool of assets. In exchange, that person receives a “private note”, which is sort of like an IOU to allow them to withdraw from the pool the same amount of crypto they put in. At some later date, they do so, using freshly-created wallets that haven’t been linked to the wallet they used to make the deposit. By pooling crypto from a large enough set of other transactions over time, it’s possible to obfuscate the link between the depositing and withdrawing wallets, which adds a degree of privacy that largely does not otherwise exist on public blockchains like Ethereum.

The process by which transactions are made private is somewhat similar to money laundering, in that funds are mixed with a large pool of transactions (illicit and licit) so as to obscure which are which. But that doesn't mean that these services are only used for money laundering. In crypto, even people performing perfectly legal transactions may wish to use these services in order to clutch back some degree of privacy that otherwise just is not supported on a ledger that publicly records every action you take. These services are also widely — some will say primarilyb — used for the type of illegal activity generally associated with money laundering: that is, concealing the proceeds of a crime. Many of the cryptocurrency heists and scams that I track at Web3 is Going Just Great end with the trail running cold as assets are laundered through Tornado Cash or similar mixing services.

Pertsev is one of several developers who wrote the code for and operated the Tornado Cash service. He was arrested and charged in the Netherlands in August 2022, and prosecutors asked for — and just got — a sentence of 64 months for his money laundering charges. When he was first arrested, I wrote:

It’s not immediately clear from the [Dutch prosecutors’] statement whether the activities that led to the arrest involved more than just contributing to the Tornado Cash codebase, but it would be very concerning if not. There are complexities around the sanctioning of Tornado Cash — a fairly decentralized software project — that raise concerns about the criminalization of code. For many, it brings to mind the “Crypto Wars” (where “crypto” is referring to cryptography rather than cryptocurrency).

It did eventually become apparent that his money laundering charge was at least in part related to his activities operating the cryptocurrency mixing service, not simply writing the code for it, which would be a more important distinction particularly in the United States, where lower courts have in the past found that the act of writing code is protected speech. And although prosecutors in the Netherlands did seem to try to avoid a strategy that would fault Pertsev for merely writing the code,1 statements from the judge in Pertsev’s sentencing seem to blur this line:c

Tornado Cash functions in the way the defendant and his cofounders developed Tornado Cash. So the operation is completely their responsibility. If the defendant had wanted to have the possibility to take action against abuse, then he should have built it in. But he did not.

[Knowledge of the tool’s illicit uses] did not refrain the defendant from developing Tornado Cash and offering it to the public without restrictions (for example by incorporating measures). On the contrary, until his arrest, he kept on developing Tornado Cash. Every next step enhanced the concealing effect and anonymity of the users. The defendant accepted the risk of the simple, unlimited, foreseeable, and evident use by criminals.

Tornado Cash combines maximum anonymity and optimal concealment techniques with a serious lack of functionalities that make identification, control or investigation possible. Tornado Cash is not a legitimate tool that has unintentionally been abused by criminals, as the defendant presents. Tornado Cash suits criminal use.2

Finding the person who wrote privacy-protecting software to be liable for merely writing that code because it was later used by criminals is extremely concerning.

Now, it is far more reasonable to me that the operators of money transmitting services should be the ones responsible for ensuring that their businesses are following relevant anti-money laundering laws that require know-your-customer identity verification, suspicious activity reporting, and other such safeguards. This broadly follows the logic that has been applied in other computer crime cases, where law enforcement will, say, prosecute people who unleash computer viruses but not those who write the virus code. And it has been the law for financial services businesses for quite some time.

However, even that gives me pause.

Privacy is a human right

If we go back to the Crypto Wars analogy, I firmly believe that people should have every right to write strong cryptographic code that allows them to, say, send an encrypted message to a friend. I also strongly believe that organizations need to be allowed to operate services that use such code — for example, Signal and its end-to-end encrypted messaging — without being held liable for criminal activity that happens on their platforms. As with most things, there are pros and cons to such a thing existing: just as these encryption algorithms allow me to protect my own, benign and perfectly legal communications from outside snooping from anyone ranging from my internet service provider to the provider of the messaging software I’m using to some government agent who might be surveilling my activities, they also protect criminals who are sending — say — child sexual abuse material (CSAM).

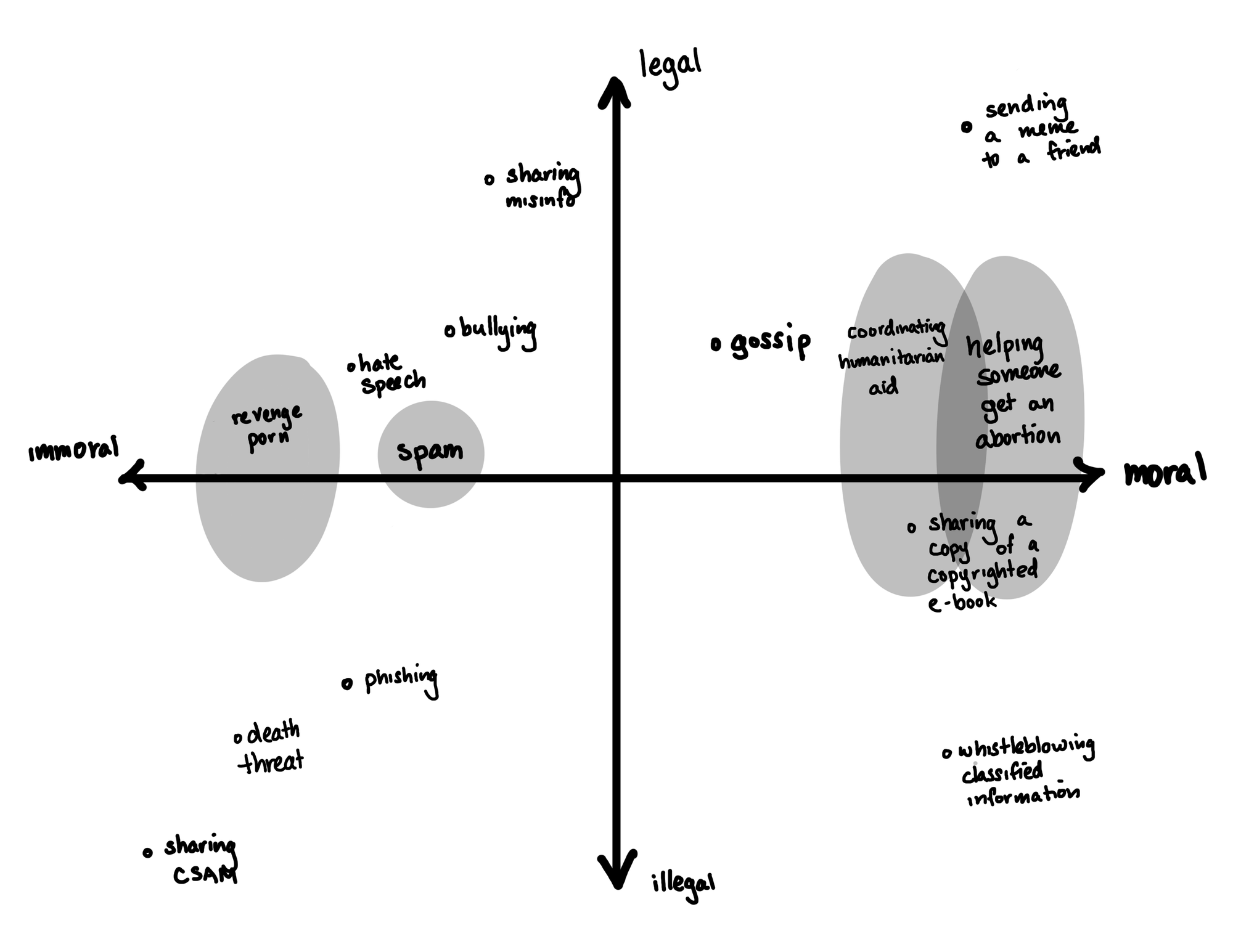

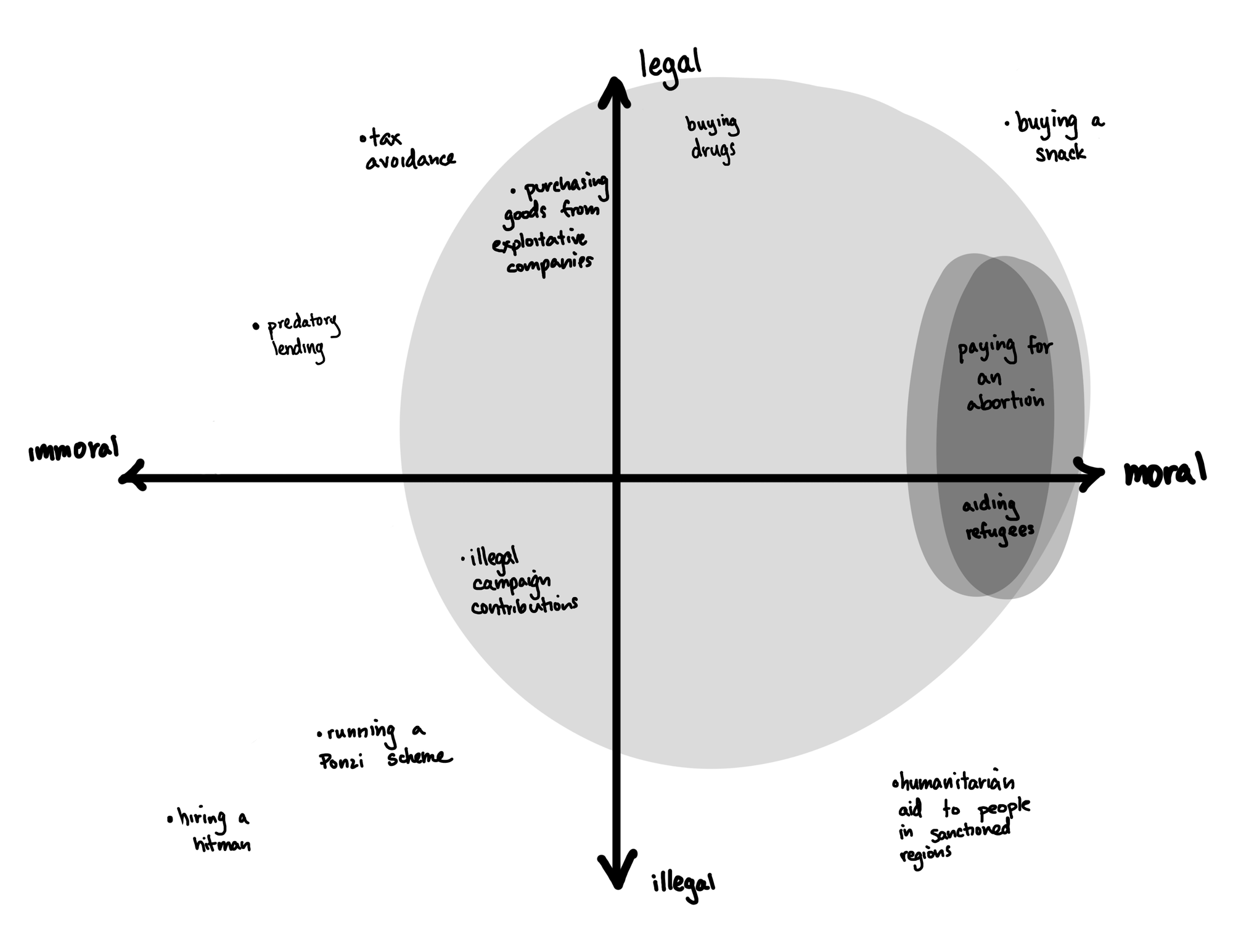

When put this way, it might seem absurd. Shouldn’t I be okay with someone snooping on the memes I send to my friend if it means that law enforcement can thwart horrific crimes?d But there’s a massive spectrum of activities, ranging from legal to illegal, moral to immoral, that must be considered.

Furthermore, what is legal in one jurisdiction at one point in time may not be legal under another, or at some other point in time. What is morally right to some people may not be morally right to others. Some things that are illegal may also be morally right, and vice versa.

There are people who have argued that companies that provide encryption software — be it encrypted messaging applications, or software that encrypts your smartphone or laptop storage — need to implement backdoors to such encryption that would allow law enforcement to compel a company to decrypt material as part of an investigation. Some activists and companies (notably Apple) have vehemently objected to these arguments, rightly pointing out that any encryption algorithm with backdoors is inherently unsafe and insecure. So far, the encryption side has mostly won out — but these are battles that continue to rage to this day, all over the world.f And my opinion is firmly on the side of strong encryption — even though the same encryption algorithms that protect human rights can be and are used for evil.

But as soon as money is involved, things are different in the eyes of the law. In the United States,g financial privacy is much weaker, if it exists at all. Unless you heavily use cash, your detailed financial activities are known to your bank or other financial institution. And the government has fairly broad access to your financial activities as well — either with a warrant, or through the types of proactive suspicious activity reporting that the government requires of these institutions.

If you do opt to use cash to try to maintain some privacy, you’re limited there also. Large cash transactions (over $10,000) have to be reported. Attempts to “structure” transactions in such a way as to avoid that reporting requirement — such as by withdrawing $9,999 at a time — are also considered suspicious and must be reported. And even if you carefully squirrel away a large stockpile of cash over time, society has developed a broad sense of suspicion around such behavior. You’re going to have a tough time convincing a person on the other end to accept cash for high-value transactions, for example. Go try to buy a house with a couple hundred thousand dollars in suitcases and let me know how it goes. Just don’t get pulled over on your way there: police routinely seize large quantities of cash under civil forfeiture procedures, solely because they assume someone carrying a lot of it must be involved in illicit activities like narcotics trafficking.

But, as with messaging, it’s easy to come up with a broad spectrum of legal and not-so-legal, moral and immoral reasons people might not want a government or other entity snooping on their finances.

Unlike with encrypted messaging, the balancing act with money has generally gone the other way. Under the law, the benefits of enabling law-abiding citizens to privately move their money around have generally not been seen to outweigh the potential costs of terrorist financing, organized crime, and the many other nasty things people do with money. As a result, although law enforcement may need to obtain a search warrant before a financial institution will turn over financial data,h there are strong requirements that that data must be collected. This is very different from encryption: firms are allowed to use end-to-end encryption for their users’ data, even though it means they can’t reveal that underlying data even if law enforcement tries to compel it.

This is something I’ve really struggled with, in large part because it all seems so arbitrary. I think people have a general right to privacy, and I do think that people ought to have financial privacy — certainly more than they have today. It’s not that I don’t see the potential harms of allowing potentially substantial amounts of money to move hands with no oversight, but the ability for governments and law enforcement to peer in on ordinary citizens is also incredibly harmful. And I think the amounts that have been determined to constitute “suspicious activity” are arbitrary and far too low, and in a digital world, incredibly challenging to reimplement.

In a perfect world, what is moral and what is legal would exactly align. Governments would always have the best interests of their citizens in mind. Law enforcement would only go after the bad guys, and leave the rest of us to go about our business.

We don’t live in a perfect world, and at least in the United States, we seem to be rocketing farther and farther away from one. We are seeing more and more attacks on human rights, particularly against marginalized groups — including the re-criminalization of abortion and related threats to reproductive healthcare, attacks on access to gender-affirming healthcare and on those who provide such care, and threats to immigrants and refugees.

Strong privacy protections are essential for human rights.

Back to cryptocurrency

Many of you know me for highlighting the scams and frauds in the cryptocurrency industry, and my related work to try to educate people about the risks associated with what I have come to view as an incredibly predatory industry. I have pushed for sensible regulation of the industry, mostly via the enforcement of existing securities regulations which should require companies in the cryptocurrency sector to undergo audits and provide transparency and accountability to consumers.

But I have long repeated that I share many of the same ideals as some — particularly the more ideologically- rather than business-motivated — in the cryptocurrency world.

Some of my earliest writings about cryptocurrency focused on the extreme privacy threats posed by many public blockchains, including my January 2022 essay “Abuse and harassment on the blockchain”, and another the following month on “Anonymous cryptocurrency wallets are not so simple”. In both of those essays, I focused on the enormous privacy threats posed by many public blockchains, which publicly expose the kind of financial information that most of us are used to having known only to our banks and governments. My concern was not that blockchains were enabling financial privacy, it was that they were promising financial privacy while accomplishing the very opposite.

I began an April 2022 essay by writing, “Some of the more ideological people who are advocating for cryptocurrencies and blockchain-based technologies are asking a lot of the right questions ... like: How can we create reasonable privacy in the financial system?”

While those fundamental opinions of mine have not changed much since I wrote those essays, things around me have. There are now a lot more cryptocurrency skeptics, both in the general public, writing the news, and on Capitol Hill. Whereas once we were generally seen to have our own independent views, I think we are now seen more as a bloc with a party line, perhaps led by Gary Gensler or Elizabeth Warren or whoever is viewed as the most prominent public cryptocurrency skeptic.

More and more, I find people assume I hold the very same opinions as those people, and are surprised when I say things like “no, I actually don’t think crypto should be banned”.i They are surprised to hear this, even though I told the Financial Stability Oversight Council two years ago that “No time should be wasted arguing over whether to try to ‘ban cryptocurrencies’ as a whole, or regulate the software that people can write or execute — a ridiculous idea.” Some of these are certainly bad-faith assumptions being made by people who see me as their enemy, and who construct some sort of statist straw-man version of me to argue with in their heads. But some of it, I think, is a failure on my part to not constantly reiterate what I think is most important, particularly as an “anti-crypto” movement much larger than me has formed.

My cryptocurrency criticism is mostly focused on educating people about two things: a technology that I feel has failed to live up to its original goals, and about the incredibly scummy industry that has emerged around it. When it comes to the regulatory side of things, I’ve mostly focused on the latter, and I care most about transparency and other consumer protections for those who do choose to get involved with crypto, as well as safeguards against impacts on the finances of those of us who don’t.j While it’s perhaps disappointing that cryptocurrency hasn’t achieved some of its more utopian financial goals, that’s not a regulatory problem.k

As for financial privacy, I am very concerned both about the lack of financial privacy afforded by cryptocurrency and the surrounding industry even as it’s widely advertised as offering more privacy than other alternatives. Every day, we see examples of how cryptocurrency tracing software — available both to the public and to law enforcement — is becoming more powerful. By choosing to use cryptocurrencies, many people are providing a public, warrantless window into their financial activities without even realizing it. Furthermore, people are rapidly learning the hard way that the cryptocurrency services they’ve used are perhaps more susceptible to surveillance than traditional financial institutions. As I explained in my Binance video:

The degree of data access by the US government as a result of [the Binance plea deal] is actually arguably overbroad, as they will now have access to user data with no requirement that the transactions raised suspicion, and no requirement that law enforcement demonstrate probable cause that that user was involved in illicit activity. Regardless of your opinions on the prevalence of crime in the crypto world, or of the likelihood a given crypto user is engaging in criminal activity, warrantless access to private data should be cause for concern.

But increasingly, I’m worried that attempts to crack down on the cryptocurrency industry — scummy though it may be — may result in overall weakening of financial privacy, and may hurt vulnerable people the most. As they say, “hard cases make bad law”.

Back to Tornado Cash

According to United States prosecutors, Tornado Cash has been used to launder billions of dollars’ worth of cryptocurrency connected to cryptocurrency hacks, including hundreds of millions of dollars by North Korea’s Lazarus Group. Prior to the criminal charges, the mixer was sanctioned by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) in August 2022.3 There’s no question whatsoever that it was heavily used by criminals to try to dodge attempts by law enforcement and crypto companies alike to trace or freeze stolen funds.

Prosecutors in the US are going to be arguing that Tornado Cash founders Roman Storm and Roman Semenov not only wrote the software to help anonymize cryptocurrency transactions, but more importantly, ran and profited from the business. As operators of a money services business, prosecutors say, it was their responsibility to know who their customers were and where their money was coming from so they could check that they were not on sanctions lists or transferring stolen assets.

Although Storm and Semenov tried a bit harder than some other cryptocurrency mixers to decentralize their operations so they could later claim that they merely wrote the code but did not operate the business, their actions may have been too little, too late. A government filing highlights the duo’s operation of the website through which the large majority of Tornado Cash transactions flowed, as well as their close control of the network of relayers.4 If these arguments hold up in court, it seems likely that they will be convicted under existing anti-money laundering laws.

And in doing so, the government will score another point against the use of cryptocurrency and cryptocurrency mixing services by bad actors and by those who are trying to achieve financial privacy for more legitimate reasons. The Lazarus Groups of the world will have a more challenging timel making off with their ill-gotten funds, and abortion funds and dissident groups and activists will have a harder time transacting privately, as well.

To be clear, I don’t think cryptocurrency is a good solution for anyone who is trying to achieve financial privacy, and there are enormous risks for those who use it for that purpose. But in a world where financial privacy is harder and harder to come by, a bad solution can be better than nothing. People who need financial privacy should not be forced to enter a digital casino and hope like hell they don't end up with their money on the next FTX. Instead, we need to work and fight for actually good, privacy-protecting solutions for digital transactions,m and stronger legislation that recognizes the importance of financial privacy.

But in the meantime, I won’t be celebrating the Tornado Cash indictments.

Footnotes

In the case of Tornado Cash, people can deposit to 0.1 ETH, 1 ETH, 10 ETH, or 100 ETH pools. If someone wanted to tumble 143.2 ETH, they would make one deposit to the 100 ETH pool, four to the 10 ETH pool, three to the 1 ETH pool, and two to the 0.1 ETH pool. This is to avoid people being able to connect two unique deposit and withdrawal amounts. At today’s prices, 0.1 ETH is around $375 and 100 ETH is around $375,000. ↩

A 2022 report by Chainalysis estimated around 30% of funds sent to Tornado Cash came from addresses known to be involved with illicit activity.5 ↩

To my (limited) knowledge there is no similar “code is speech” precedent in Dutch law. ↩

Or a similar argument: “why should you care about someone snooping on you if you’ve got nothing to hide?” ↩

This is just a rough scribble of where I think some of these things should go. Reasonable people can certainly disagree. ↩

For example, a recent bill in the United Kingdom gives broad authority to Ofcom to order technology companies — including ones that use end-to-end encryption — to scan for material such as terrorism content or CSAM on their services, even as the government has acknowledged they have no privacy-protecting way to do such a thing. ↩

And elsewhere, but I’m mostly familiar with and speaking about the US here. ↩

But not necessarily — as I mentioned earlier, financial institutions are required to report all transactions of more than $10,000 a day, as well as other transactions they deem suspicious. ↩

For example, I worry a lot about financial contagion as traditional financial institutions get more and more involved with crypto assets, and the ill effects this could have during another crypto collapse on people who don’t even realize they’re exposed to crypto risk. ↩

Except insofar as cryptocurrency companies have a penchant for lying about having achieved these utopian goals, which I suppose might be an issue of false advertising. ↩

Not that challenging, though. As mixing services come and go, cybercrime groups have had no apparent problems adapting. ↩

There have been proposals for non-blockchain-based digital money which would have similar privacy features as cash, such as E-Cash. ↩

References

“Developer of Tornado Cash gets jail sentence for laundering billions of dollars in cryptocurrency”, Rechtbank Oost-Brabant. ↩

“U.S. Treasury Sanctions Notorious Virtual Currency Mixer Tornado Cash”, U.S. Department of the Treasury. ↩

Memorandum in opposition filed on April 26, 2024. Document #53 in US v. Storm. ↩

“Understanding Tornado Cash, Its Sanctions Implications, and Key Compliance Questions”, Chainalysis. ↩