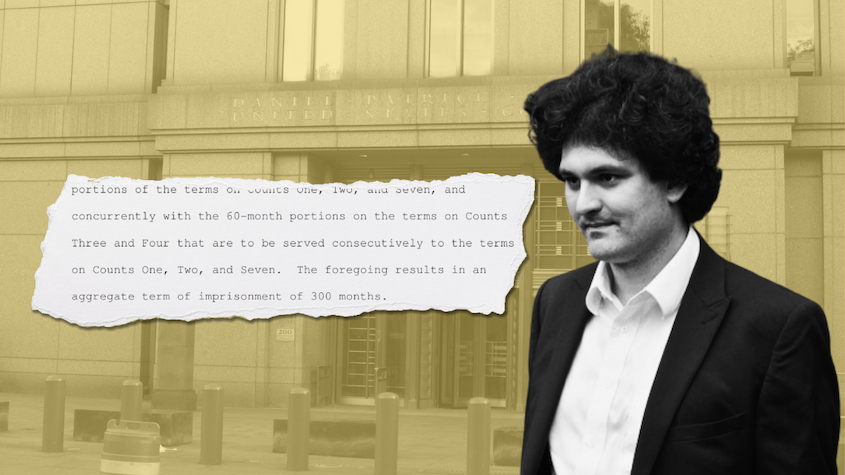

25 years for Sam Bankman-Fried

"The judgment has to adequately reflect the seriousness of the crime, and this was a very serious crime."

Just like the jury deliberations, Sam Bankman-Fried's sentencing was brief. Commencing at 9:30, the sentence was delivered before noon.

The judge began the sentencing hearing by ruling on a few points of contention from the sentencing memorandums, after which he established Bankman-Fried's numeric offense level.

The most substantial disagreement was on the topic of the loss amount. The government contended that the total loss to FTX's customers and investors and to Alameda's lenders was $10 billion, on the low end. The defense argued that the loss was zero. Many pages in each side's sentencing memorandums were devoted to arguing over this.

The judge was quick to rule: "I reject entirely the defendant's argument that there was no actual loss." The claims that customers and creditors will be repaid is at this point purely speculative, as the bankruptcy proceedings are still underway. He added that while the success of some of Alameda's investments,a and the recent rise in cryptocurrency prices, is fortuitous for creditors, it does not make Bankman-Fried's crimes any less severe. As he is wont to do, the judge provided an analogy:

A thief who takes his loot to Las Vegas and successfully bets the stolen money is not entitled to a discount on the sentence by using his Las Vegas winnings to pay back all or part of what he stole if and when he gets caught.

Judge Kaplan ultimately decided that the loss in this case well exceeded the upper bound of the sentencing table, which maxes out at $550 million, and that the 30-point sentencing enhancement was justified.

Additional, smaller enhancements were also discussed, and all were decided in favor of the government. While the defense had originally argued that there were no victims in this case, Bankman-Fried's attorney asserted that they had made that claim before receiving the victim impact statements — though he stopped short of withdrawing the argument. "So you're not withdrawing the position, but you're really signaling me that you fully understand there's not much merit to it," said Kaplan, ultimately agreeing with the government that there were more than 25 victims who suffered "substantial hardship".

More points were tacked on for sophisticated means, deriving $1 million from a financial institution, conviction on 18 U.S.C. § 19561 (money laundering), leadership role in the offenses, and abuse of a position of trust.

When discussing the government's proposed sentencing enhancement for obstruction of justice, Kaplan first referenced Bankman-Fried's attempt at witness tampering in January 2023 [I18, I36]. Although that alone was enough to justify the enhancement, Kaplan also described three specific instances in which he determined Bankman-Fried had committed perjury while testifying:

- Claiming that he did not know Alameda Research had spent FTX customer deposits until fall 2022

- Claiming that he first learned of Alameda's $8 billion liability to FTX in October 2022

- Claiming that he did not know repaying Alameda's loans in mid June 2022 would require Alameda to borrow from FTX

Kaplan noted several times that this was not an exhaustive list of the instances in which Bankman-Fried had perjured himself, but that those alone justified the enhancement.

Kaplan finally announced the offense level for Bankman-Fried: 60. This was what the government had requested, and was four points more than what was described in the pre-sentence report. The sentencing guidelines top out at a maximum of 43 points, which corresponds to a life sentence even for first-time offenders. However, the statutory maximum for Bankman-Fried's charge was 1,320 months (110 years).

Although Kaplan's findings seemed enormously bad for Bankman-Fried's prayers for a lighter sentence, Kaplan did provide one ray of hope for Bankman-Fried: his skepticism of the loss table and its use in calculating sentences. He noted that the table was "a debatable proposition", and one that does not bind him in his sentencing. "As I understand its genesis, there's really no empirical basis for the brackets assigned or for the assignment of different losses to different brackets."

Before delivering his sentence, victims were given the opportunity to speak, then Bankman-Fried's lawyers, then Bankman-Fried, and then the prosecutors.

Victims

Only one victim appeared in person to deliver a victim impact statement, despite hundreds being filed. Sunil Kavuri, an outspoken FTX creditor who lost more than $2 million in the collapse, who has served on various creditor committees, and who is a part of the lawsuit against FTX's high-profile promoters, traveled from London to speak in person.

While he spoke in his testimony of his personal suffering, and that of other creditors, he spent most of his allotted time condemning the FTX bankruptcy estate and lawyers, claiming they seemed to be working "intentionally to destroy our value". He quickly got deep into the weeds of some of the disputes in the bankruptcy, accusing Sullivan & Cromwell of selling Sui tokens and other assets at a loss. Kaplan eventually intervened, informing Kavuri that "The points you are now raising, it seems to me, are issues for the bankruptcy court."

At that point, Kavuri spoke briefly about emotional and mental distress before lapsing back into his accusations against the bankruptcy team, at which point Kaplan asked him to wrap it up.

Lawyers for the multi-district litigation against FTX, with which Kavuri is involved, also spoke briefly — though they took their time to thank Bankman-Fried for being helpful in their suit.

The defense attorney

Bankman-Fried's lawyer, Mark Mukasey [I49], delivered the statement for the defense team. Though briefly stating that his team and Bankman-Fried were sympathetic to the victims and their pain, he launched into a hagiography of Bankman-Fried in which he portrayed him as a good, kind, and beautiful person.

Really, he's an awkward math nerd. He thinks in probabilities about everything. He speaks in expected value calculations. He loves video games and veganism, and he's compassionate to animals and children. And he has a tireless work ethic. ... Sam himself is sort of a beautiful puzzle. He's at once hyperrational, but not cold or robotic. He's super focused on some things, but completely absent minded about other things. He can parse words better than a talmudic scholar, but he can completely misread the surroundings. He can concentrate like a laser beam, but also be fidgeting at 100 miles an hour. He was a billionaire, but completely unconcerned about material possessions.

He contrasted this portrait of Sam Bankman-Fried with the "stone cold financial assassins" and "ruthless financial serial killer[s] who set out every morning to hurt people", saying that Bankman-Fried is "not the defendant who looks someone in the eye while he took money out of their pocket."b

He gestured to Bankman-Fried's continued claims that FTX and Alameda Research were solvent as of the time of bankruptcy, though he stopped short of endorsing them himself: "I think he's firm in his belief that he may well have been able to solve what he viewed as a black swan liquidity crisis."c

He repeated arguments from the sentencing memo that Bankman-Fried had already been punished. He's "lost everything," said Mukasey. His time in jail has been horrific, as jailtime is for everyone.

Finally, he asked for lenience, appealing to sympathy: "I'm asking the Court not to destroy the prime of this complicated, brilliant, gentle, complex, kind young man's life. Don't deprive him of the opportunity to meet a partner or have a baby or work at a charity or teach kids or use his beautiful mind."

Mukasey did a halfway decent job, I think. Better than Bankman-Fried's previous, somewhat bumbling defense team. But even more capable lawyers apparently couldn't stop Sam Bankman-Fried from being Sam Bankman-Fried.d

Sam Bankman-Fried

Sam Bankman-Fried's typical speaking style is a meandering, stream-of-consciousness ramble, and today was no exception.

He began by acknowledging Sunil Kavuri's victim statement, even agreeing with him that funds were being squandered by the bankruptcy team. He repeated his tired claims that the money is all still there, and claimed that the estate has billions of excess dollars with which it could repay all creditors in-kind or at current crypto prices, and reimburse investors.

He spoke of his mistakes, but then explained that he was referring to his decision to declare bankruptcy and relinquish control of the company — not to the decision to misappropriate billions of dollars of customer assets. He acknowledged that he was among the people who had "failed" customers — but couldn't help but spread the blame around to some others, too.

And he ended his statement in a bizarre and probably ill-advised way: by claiming that "there is a big opportunity in the world to do what the world thought I would do" — that is, start a lucrative cryptocurrency business.

The prosecution

Prosecutor Nick Roos was clearly listening intently to Bankman-Fried's and his lawyer's statements, and referenced them several times in his own statement to underscore why he believed Bankman-Fried needed to be sentenced to at least forty years.

I was struck at the end by the comments that there is an opportunity here, that there is an opportunity that someone, maybe his former coworkers, maybe someone else, could relaunch FTX, or something of an equivalent and, without the mismanagement or the liquidity crisis, things could work out... the defendant's statements today express not one of acceptance of responsibility but one of recognizing errors that, had they not been committed, could have let him get away with it for longer, so a sentence here is necessary of at least 40 years to ensure that the defendant cannot do it again.

Roos pushed back against Bankman-Fried's claims that the collapse was simply a "liquidity crisis or an act of mismanagement or poor oversight from the top", as established at trial.

He countered Mukasey's argument that Bankman-Fried isn't the type of defendant who looks people in the eyes while stealing from them. "I disagree ... because nowadays a defendant can look people in the eyes through Twitter, through social media, through the Internet. And that's exactly what happened here. He told them their money was safe. He said trust me."

Roos described destroyed lives, bankrupted companies, and lost jobs.

And finally, he described the likelihood that Bankman-Fried would reoffend. He pointed to Bankman-Fried's misconduct while on pre-trial release, his efforts and ideation around rebranding himself, and his statements about creating a new cryptocurrency exchange. He drew upon the defense's own statements that Bankman-Fried acts not with malice, but with math: "While the line sounds good, it's troubling because what it says is that if Mr. Bankman-Fried thought the mathematics would justify it, he would do it again."

The sentence

Kaplan, again, seemed to largely agree with the government's description of Sam Bankman-Fried. He described Bankman-Fried's political donations, underscoring that they appeared motivated by Bankman-Fried's desire to raise his own profile and influence, not to advance any particular political causes. He explained that he viewed Bankman-Fried's lobbying in favor of crypto regulations as "an act" — and noted that he ultimately admitted that in conversations with a journalist that he would later claim he didn't think were on the record. "Fuck regulators," he said to her.

He was skeptical of Bankman-Fried's anemic statements of remorse, which his defense team tried to characterize as acceptance of responsibility. His behavior on the stand also clearly influenced Kaplan, who said that in his nearly thirty years as a judge, he'd "never seen a performance quite like that". "[W]hen he wasn't outright lying, he was often evasive, hairsplitting, dodging questions and trying to get the prosecutor to reword questions in ways that he could answer in ways he thought less harmful than a truthful answer to the question that was posed would have been."

Finally, Kaplan explained that he shared the prosecution's concern that Bankman-Fried would reoffend. "There is absolutely no doubt that Mr. Bankman-Fried's name right now is pretty much mud around the world, but one of the things he is is persistent, and another of the things he is is a great marketing guy," said Kaplan. His media tour, pre- and post-arrest, demonstrated that he knew how to present a revised version of events. "The mistakes were made, other people are to blame, the bankruptcy people screwed up, this lawyer had a conflict of interest, that lawyer the other thing. [It] doesn't take much of an intonation to see the outlines of the campaign." Kaplan explained that his ultimate sentence would be, in part, focused on making Bankman-Fried unable to embark on such an endeavor.

He wrapped up: "The judgment has to adequately reflect the seriousness of the crime, and this was a very serious crime."

In the end, I think it may have been Kaplan's views around the efficacy of lengthy sentences that may have saved Bankman-Fried from a sentence of the length proposed by the prosecution. Judges are also rather well known for splitting the difference between proposed sentences offered by the prosecution and the defense, and he did so here. Ultimately, he sentenced Bankman-Fried to 25 years in prison and a monetary judgment of $11 billion. He recommended Bankman-Fried be designated to a medium- or low-security prison, preferably near his family, based the belief that Bankman-Fried is not likely to be violent and based on concerns that Bankman-Fried's notoriety, association with vast wealth, autism, and social awkwardness could make him particularly vulnerable in a maximum-security environment.

Reaction

It was not surprising to me that most onlookers,e many of whom were quite justifiably furious at the harm Bankman-Fried has inflicted, were upset at what they saw as undeserved lenience. Many had hoped to see a 40–50 year sentence, some believed that the 100-year sentence described in the pre-sentence report was justified, and some went even further: expressing their wishes that he would face life in prison, or even harsher punishments than that.

I saw various observers describe his sentence as "a slap on the wrist" or a "light sentence".

While I understand why people had hoped for a lengthier sentence, I don't think it's in any way reasonable to describe a 25-year sentence as a slap on the wrist. 25 years in prison is a horrific ordeal no matter how you look at it. 25 years ago, Sam Bankman-Fried was seven years old. In another 25, he'll be 57. That's an enormous and meaningful portion of a person's life, and Bankman-Fried will spend it locked in a prison cell in conditions ranging from horrific to poor, depending on where he winds up.

Bankman-Fried's victims suffered horrific ordeals, and so too will he.

However, I acknowledge that much of my reaction stems from my own opinions on prisons, and my general belief that extremely lengthy prison terms offer diminishing returns.f I'm skeptical that a 40-year sentence would be any more successful in deterring other would-be offenders, or in deterring a person from reoffending — except insofar as it increases the risk that that person dies in prison before they have an opportunity to reoffend.

As for the monetary judgment, he is unlikely to ever be able to pay it, and is likely to have wages garnished if he does find employment after release.

What next?

There are a few questions remaining at this juncture.

The first is the question of appeal. We already know that an appeal has been in the works at least since Bankman-Fried was convicted, and his lawyers today confirmed he still intends to appeal. My suspicion is that he won't find much success in this. His previous defense team didn't cover themselves in glory during his trial, but I think much of that can be blamed on the tough case in front of them rather than ineffective counsel. The ultimate sentence also seems well within the bounds of reason, and if anything comes off as lenient when compared to the pre-sentence report. I suspect that both the conviction and sentence will be upheld on appeal.

The second is the question of how much of the sentence Bankman-Fried will actually serve. As I wrote previously, most federal offenders have to serve around 85% of their sentence before becoming eligible for early release. In Bankman-Fried's case, this means 21¼ of the 25 years. However, one potential avenue for Bankman-Fried may be the 2018 First Step Act, which could allow him to reduce his sentence by another year, and could allow him the opportunity to earn substantial good-time credits that could result in him spending a substantial portion of his sentence — around half — in home confinement or a halfway house. I once again will note that I'm not a lawyer, and so I'm not entirely sure if factors such as — say — Bankman-Fried's previous disastrous home confinement would play a role in his eligibility here.

Finally, there's the question of the remaining litigation against him. In addition to the multi-district litigation I mentioned earlier, Bankman-Fried is also a defendant in lawsuits filed in bankruptcy court. There's also the issue of the civil cases against him from the SEC and the CFTC. Both of these were stayed as the criminal case played out, but will resume now that it's been decided. With evidence already established at trial, the path to a judgment seems straightforward. I have my doubts that they will pursue substantial additional restitution on top of the $11 billion judgment ordered in the criminal trial, but it strikes me as quite likely they might pursue an injunction preventing Bankman-Fried from holding positions of power in future companies, or from working in the securities industries or trading securities or commodities.

Footnotes

Particularly Alameda Research's $500 million investment into the AI company Anthropic, a stake which has been more recently estimated to be worth $1.4 billion. The FTX estate has recently disclosed that they've lined up buyers who will purchase around two thirds of those shares for $884 million, subject to approval by the bankruptcy court.2 ↩

This was unfortunate wording, in my view, after the defense team has spent such a long time emphasizing Bankman-Fried's challenges with making eye contact as a result of his autism. ↩

Item #13 on Bankman-Fried's private "random probably bad ideas" Google document was "Lean in to the story 'really it was because of tail risk crashes, this was improbable, NAV was like +$50b earlier this year'", so I personally am skeptical this isn't just one of his many manufactured narratives that he's calculated might help him save face. ↩

I am making assumptions here — it's of course possible that Mukasey coached Bankman-Fried to say exactly what he said. I suspect not, though. ↩

Most American onlookers, that is. I did see some commenters from outside of the US expressing shock that Americans view a 25-year prison term as lenient. ↩

It's also important to note that I don't believe prison reform should begin with the Sam Bankman-Frieds of the world. While I think the downward departure in sentence length was reasonable here, I also have to note that there are many people — generally with far less privilege than SBF — serving substantially longer sentences for much less severe crimes. Prison reform that only benefits white collar criminals and/or those who are wealthy, white, and well-connected is not prison reform at all. ↩