We can have a different web

Many yearn for the “good old days” of the web. We could have those good old days back — or something even better — and if anything, it would be easier now than it ever was.

As a lifelong lover of the web, it's hard not to feel a little hopeless right now.

Search engines — the window into the web for many people — top their results with pages containing thousands of words of auto-generated nothingness, perfectly optimized for search engine prominence and to pull in money via ads and affiliate links while simultaneously devoid of any useful information.

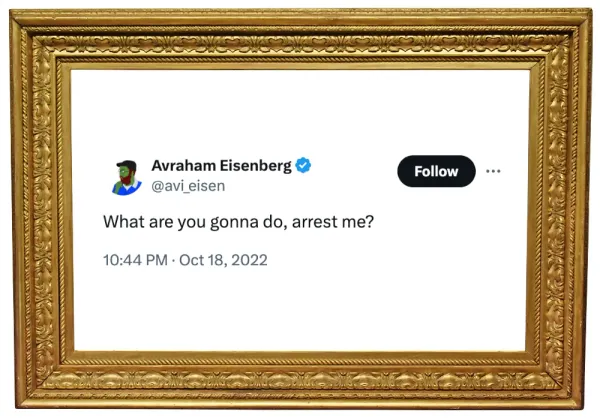

Social networks have become “the web” for many people who rarely venture outside of their tall and increasingly reinforced walls. As Tom Eastman once put it, the web has rotted into “five giant websites, each filled with screenshots of the other four”.1 Within those enclosures, the character limits, neutered subset of web functionality, and constant push to satisfy the enigmatic desires of an algorithm tuned to keeping eyeballs on the platform encourage sameness, vapid engagement farming, and rage bait while stifling creativity.

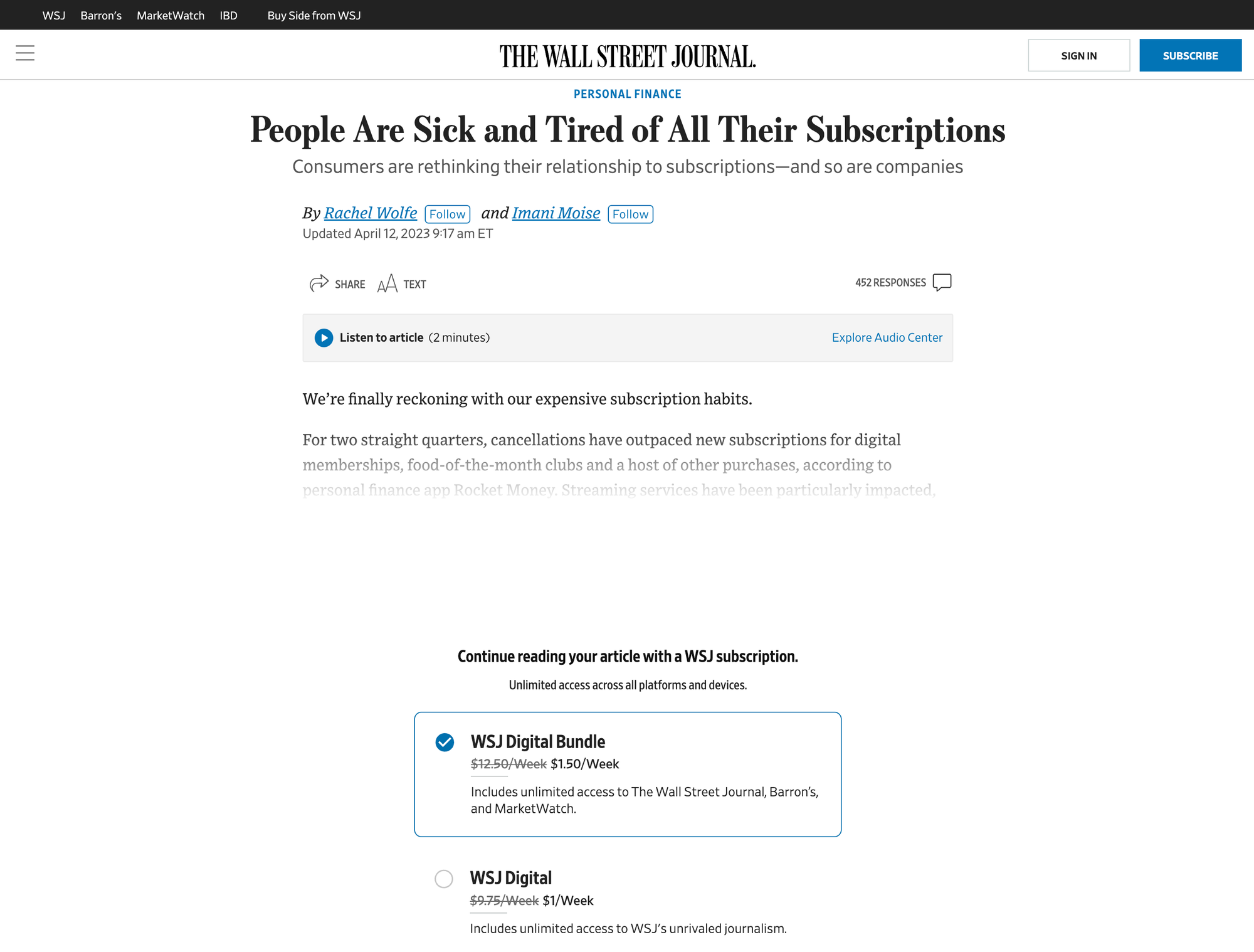

Newspapers, whose evolution towards online models once stoked optimism for more accessible and dynamic journalism that could lead to a more informed and democratically engaged citizenry, have become luxury goods as aggressive paywalls and expensive subscription models are increasingly deployed by the hedge funds and other profit-hungry entities that control these papers. Some use the excuse that they're trying to protect their journalism from the unsanctioned scraping by companies training ever-hungrier artificial intelligence models. Yet those same media outlets hasten their own demise with wave after wave of layoffs, or by chasing harebrained schemes like churning out tedious clickbait or their own AI-generated soup even as their executives continue to cash huge checks.

Many websites now require one to steel themselves for battle against the advertisements and trackers and GDPR cookie consent popups and AI-powered chatbot windows that interrupt you to offer to helpfully bungle whatever you ask of them. AdBlock is no longer optional, and even with it, trackers and advertisements slither through the cracks. Browsing the web brings with it the ever-present feeling that you're being watched — your activities and preferences and habits all being logged and funneled into a giant vat of horrifying data soup, all just to help more companies serve you more of these intrusive ads that you must endlessly swat away as you try to find whatever it was you were looking for.

It is tempting, amid all of this decay, to yearn for the good old days.

The emergence of online chat and instant messaging, where you used some acronym-named chat like ICQ or IRC or AOL messenger to talk to friends you knew in real life or anonymous strangers all over the globe. Those phpBB forums and message boards on sites like GameFAQs — or, for some, the BBSes and Usenet newsgroups that predated them. The flash games and the whimsical GeoCities sites full of dancing hamsters and the MySpace pages full of garish, hand-coded styles and glitter GIFs and auto-playing MIDI tracks.

Those incredibly specific websites created by one guy with an encyclopedic knowledge of something really niche, or the labors of love that were fansites dedicated to The X Files or the Backstreet Boys.

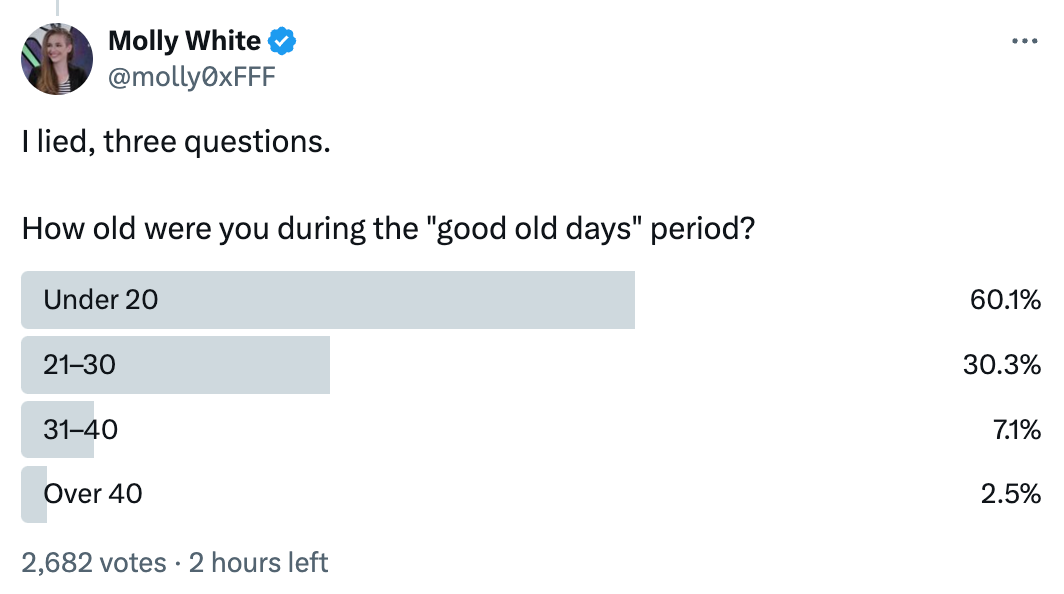

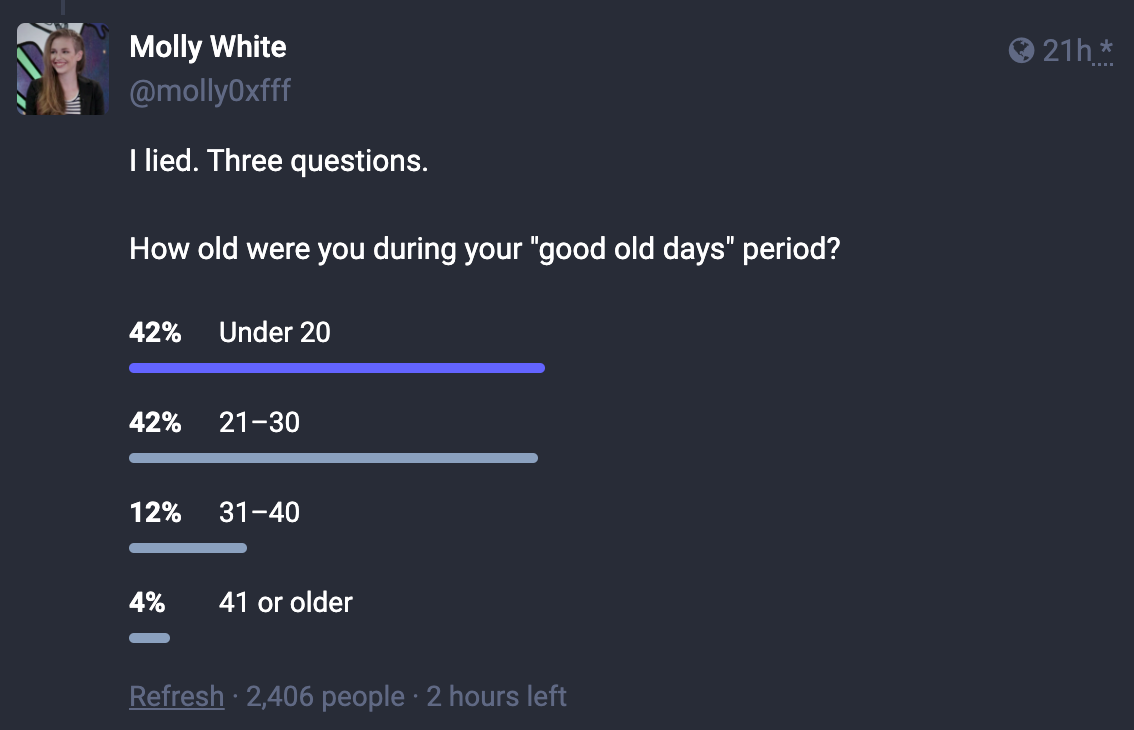

Some of this is nostalgia for our younger years, I think. According to my very scientific Twitter and Mastodon polls, around 60% and 42% (respectively) of people happened to be under 20 years old during the period they identified as the "good old days".

It may be that we are, at least in part, yearning for the days when logging on to the internet was less likely to mean going to work or paying a bill and more likely to mean playing Runescape or hoping that the green circle on AIM would light up next to the name of our crush after school.

But some of this is certainly based in the feeling that the web was just better back then. Fewer trolls, and a lot fewer bots. Google search results that actually returned what you were looking for, not just the sites that paid the most. Cobbled-together blogs and LiveJournal pages written by people who felt authentic, who maybe wanted to attract more visitors to tick up their pageview counters or add entries to their guestbook pages, but who weren't trying to cultivate a persona as an influencer or a thought leader, "build a brand", or monetize their audience. More of a neighborhood feeling where everyone was a possible friend, and less fear that people might interpret your social media post as uncharitably as possible. The worry that the girl you were talking to might be a man pretending to be a girl, but probably not the fear that she's a crypto romance scammer or part of a state-sponsored disinformation network. Fewer and less intrusive ads, less engagement farming, less surveillance. Fewer paywalls, more "information wants to be free".

The thing is: none of this is gone. Nothing about the web has changed that prevents us from going back. If anything, it's become a lot easier. We can return. Better, yet: we can restore the things we loved about the old web while incorporating the wonderful things that have emerged since, developing even better things as we go forward, and leaving behind some things from the early web days we all too often forget when we put on our rose-colored glasses.

When I envision the web, I picture an infinite expanse of empty space that stretches as far as the eye can see. It's full of fertile soil, but no seeds have taken root. That is, except for about an acre of it.

Years ago, in the web's early days, people entered this infinite expanse and began to cultivate it. First it was the scientists at CERN, who poked a hole through into this uncultivated world and began to experiment within that acre. Eventually, they widened the entry point to enable others — mostly from universities — to join. They set up their own tiny plots within this acre, sowing seeds that they personally loved.

With time, the entrance widened even further, and geeks outside of universities found their way in. Then, home computing really began to take off, and the number of visitors expanded far beyond just the geeky hobbyists. Some people continued to cultivate their own little patches in the acre, but others opened community gardens: forum sites and shared blogs and chat rooms and webhosting services where people could develop their own projects. People brought in little gnome sculptures and garish lawn flamingos. Some people erected fencing to control who wandered in — or even who could see in — to their plots. But people had also begun to build pathways in the spaces among the patches: webrings and hand-curated blogrolls, vigorous hyperlinking, and early versions of search engines.

There were weeds, too. Invasive plants that threatened to crowd out what some people had lovingly built. Trolls that poisoned the forums and chat rooms, or the threat of viruses that made people more cautious. All too many people who shunned or harassed those who didn't fit the mold of the (white, male, straight) prototypical internet user.

And some from the outside world began to worry. What do you mean there are no police there? And you're letting kids in? Hey, those are my seeds you're using, and now you're just giving them away for free to other people!

But eventually, businesses set up shop, selling everything from seeds to tractors to garden gnomes to landscaping services to all the kinds of things people were used to using back outside of this digital expanse. And at first, they fit in among the hobbyist plots and community gardens.

But with time, businesses learned there were other ways to extract money from the community that had grown within this acre in the digital world. They set up tolls on the pathways. They planted invasive species that encroached on what other people had built, shading them out — or they spread pesticides that poisoned what others had cultivated. Some acquired plot after plot after plot, building their own empires through which others needed to pass to get where they were trying to go. Many businesses initially invited people in with open arms, promising that if they moved within their boundaries, the business would take care of all the hard stuff — the digging, the weeding, the sowing — and let you just do the parts you wanted to do. After a time, many people opted to do so, drawn in by these easy and free services that let them spend more time admiring the flowers or visiting neighbors and less time doing the dirty work. But then, the walls went up.

Towering over the rest of the acre, massive walls shaded out much of what was happening outside of these businesses' enclosures. People couldn't see over to know what was happening beyond, so was it even worth the effort to make a visit? After all, there's so much to see inside. These businesses set up right at the gate too, so some new entrants thought the space within the walls was all there was. They never saw the infinite expanse beyond, nor the creativity that was still flourishing out there.

Some pathways remained, mostly linking together these giant fortresses, but with time even those were made harder to pass. Rules were imposed to limit what plants you could grow and how you could grow them and who might ever be able to see them. Some maintained plots within multiple of these businesses' walled areas, but found themselves having to devote more and more of their time to maintaining all of their disparate gardens, or let some of them lie fallow.

The businesses developed systems to quickly usher people along from undesirable tenants, drawing their attention to the carefully manicured plots where nary a blade of grass was out of place. And they started checking IDs at the door, making sure you were known both to the business owners and the policemen who had set up watchtowers and CCTV networks. Increasingly, drones passed overhead, operated by businesses who peered in to see what kinds of plants you were growing and what kinds of decorations you were putting up in hopes of selling you something similar later on.

If a tenant decided they were sick of their spot within a walled garden, well, they could leave — but it meant they abandoned what they had built, and the path for friends or admirers of their work to come visit them became a lot more arduous to traverse.

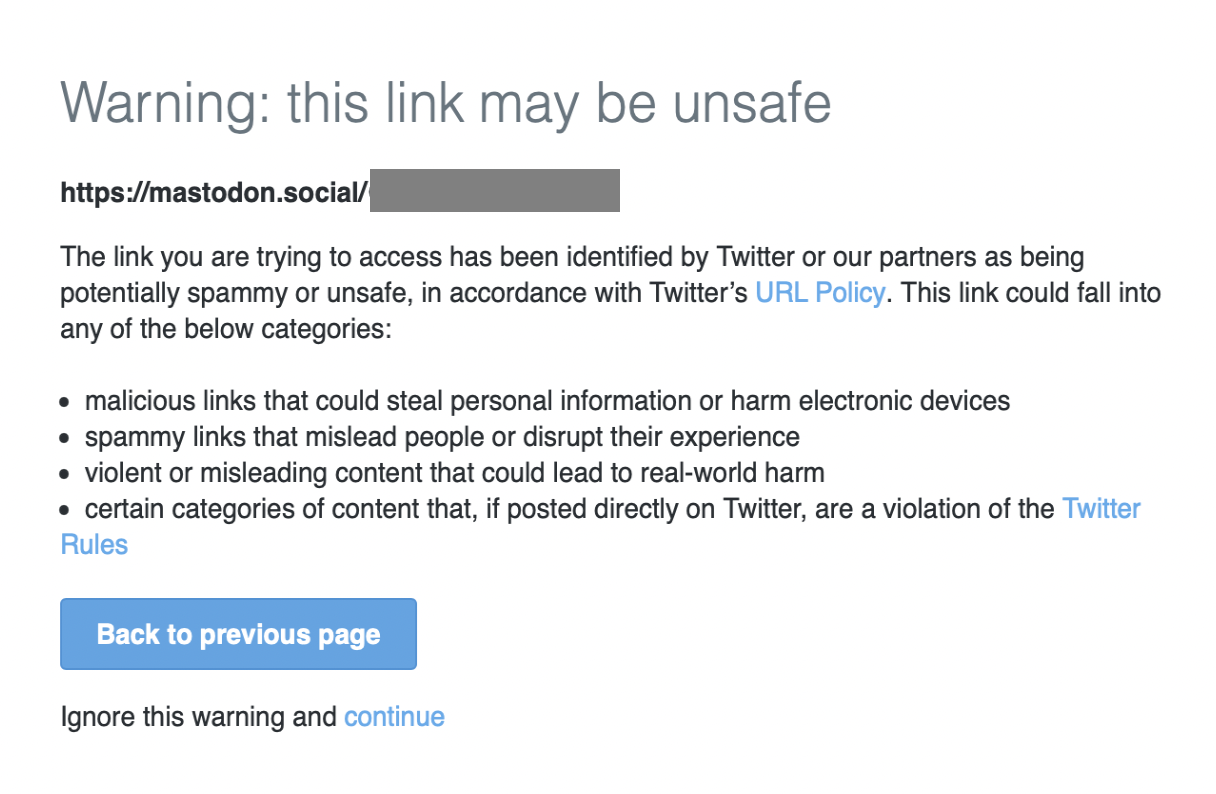

This is the world of today's web. Most of us spend our days within the confines of a handful of platforms, wandering around to admire what people have done with the seeds they are allowed in the space they are allotted, with platform owners directing us to the gardens they think we might like — or, more often, the ones they think will keep us within their walls for longer. Occasionally we venture outside to another plot, but sometimes we're given dire warnings before we go. After all, there could be weeds out there!

And those who cultivate those plots outside of these walls face pressures to conform to the whims of the businesses in hopes that the pathways remain open. Otherwise, they might toil away in silence, rarely seeing visitors like they one day used to.

It feels grim, and especially so for those of us who remember the days before the walls. We miss the messy but innovative landscaping, the use of space beyond the tiny squares our landlords provide us, the mostly polite strangers who wandered through and remarked on our work or shared their knowledge with us.

But we often forget: that world is still out there.

The walled enclosures that crowded out much of that acre of developed land still reside within an infinite expanse of possibility. There are no limits to the web — if it has borders, they are ever expanding. We may feel as though we are trapped in a tiny, crowded, noisy space, but it is only because we don't see over the walls.

If we wanted, each of us could escape those walls and set up our own spaces within the limitless, fertile soil beyond. Some of us might opt to leave those walls permanently, while others might choose to split our time between our beautiful, messy, free world outside to maintain smaller, meticulously-groomed simulacrums within the enclosures that hint — without angering our landlords — at the creations beyond. We can periodically smuggle seeds and plant cuttings beyond the walls, ensuring that if the proprietors decide to evict us, our gardens will live on.

We can develop protocols — more resilient versions of those early footpaths — that inherently resist the tollbooths and border crossing gates established by the businesses with the walls. We can even develop our own community gardens with spaces for tenants that have their own models of governance far beyond the single benevolent platform dictatorship model — that inevitably grows less benevolent as money changes hands.

While some of the early gardens that we reminisce about didn't survive the shade of the large platforms or the dwindling flow of visitors that were rerouted within those walls, new gardens can be cultivated to their specifications. People can experiment with combining the things they loved about the old gardens with the tools and models of the ones that have grown since then, or return to the spirit of experimentation and try new things altogether. They can draw on the population explosion within the digital expanse to bring in new people with new ideas and new energy to revitalize what once was, and make it better than before.

Though we now face a new challenge as the dominance of the massive walled gardens has become overwhelming, we have tools in our arsenal: the memories of once was, and the creativity of far more people than ever before, who entered the digital expanse but have grown disillusioned with the business moguls controlling life within the walls.

And if anything, it is easier now to do all of this than it ever was. In the early days, people had to fight to enter the expanse at all, and those who did were starting with little. Now, the expanse feels ubiquitous in some countries, and is becoming ever more accessible in the others. Sophisticated tools and techniques are available even to novices. Where once the walled gardens were the only viable option for novice gardeners or those without many resources, that is no longer so much the case — and the skills and resources required to establish one's own sovereign plot become more accessible by the day.

We can have a different web, if we want it.

Further reading

- “The Internet Is About to Get Weird Again” by Anil Dash in Rolling Stone.

- “A Brief History & Ethos of the Digital Garden” by Maggie Appleton. Her beautiful illustrations are what I think of when I picture the digital expanse, and the feature image is inspired by her “avoid walled gardens” illustration in this post.

- “We Need To Rewild The Internet” by Maria Farrell and Robin Berjon in Noema.

- The indie web, the cozy web, the small web

- The incredible variety of responses by people on Twitter, Mastodon, and Bluesky when I asked them what they miss about the “good old days” of the web